At the recent Mid-Atlantic Association of Museums (MAAM) conference in Pittsburgh, I attended “Headwinds and Tailwinds: A Panel Discussion about the Financial and Operational Impacts on the Museum and Arts Management Field.” One of the panelists, Hayley Haldeman of the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, offered particularly insightful observations about board governance in the post-COVID landscape. Her comments confirmed what many of us have observed firsthand—museum boards are facing more challenges and opportunities than ever before.

A Changing Landscape—But Familiar Structures

Despite the upheavals of recent years, Haldeman noted that few organizations have made major changes to their board structures. Most boards remain large, and many governance documents have yet to be updated. The notable exception has been a growing emphasis on board diversity—though progress toward real inclusion varies widely.

At the same time, museums are experiencing significant leadership transitions. Many long-serving executive directors have retired, while others are navigating the aftermath of the “Great Resignation,” which has affected both staff and board leadership. These changes can be destabilizing, but they also open the door for renewal.

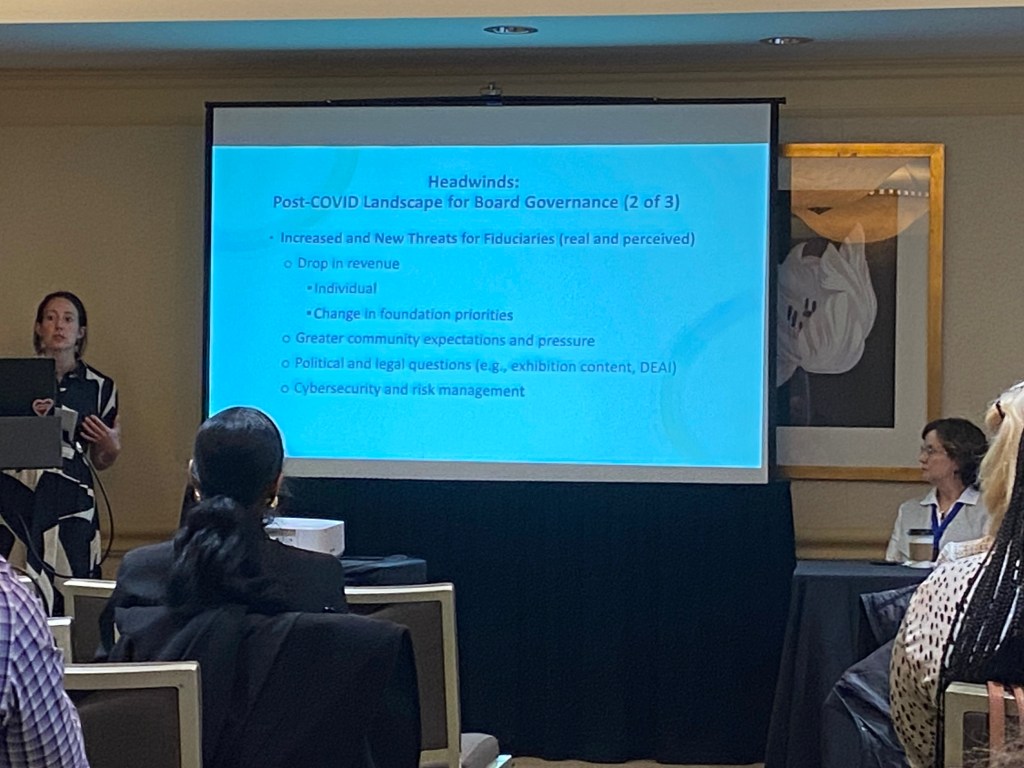

New Pressures on Museums and Nonprofit Organizations

Board service today comes with new (and sometimes unexpected) responsibilities. Museums and other nonprofit organizations are grappling with a range of threats, both real and perceived:

- Drops in individual giving and shifts in foundation priorities

- Greater community expectations for accountability and transparency

- Political and legal questions (e.g., DEAI initiatives, exhibition content)

- Cybersecurity and AI-related risks

Meanwhile, board members are harder to recruit and retain. COVID-19 reshaped personal and professional priorities, making time an even scarcer resource. For organizations, that means it’s harder than ever to fill board seats, onboard new members, and keep them engaged—especially when board work happens virtually.

Time for a Governance Audit

Haldeman encouraged organizations to treat this moment as an opportunity for a governance refresh. Start with a fundamental question: What do we need from our Board?

- Time: Are we using board members’ time efficiently and effectively? Remember that their time also equates to staff time.

- Treasure: Are we recruiting someone for their potential donation, or could we cultivate them as a donor without a board seat?

- Talent: What expertise, connections, or community insight do we need most right now?

From there, take a close look at whether your governance structure reflects your current needs. For mid-size to large boards, committees can act as the real workhorses—where expertise and engagement meet. Review which committees are essential and which can be sunset. Consider whether temporary task forces might serve specific projects more effectively than creating standing committees with no clear end.

A useful rule of thumb: the number of board members should roughly equal one-third the size of your staff. For example, an organization with 60 staff members might function best with a 20-member board—large enough for diversity of thought, but small enough to remain nimble and manageable.

The Governance Refresh

A comprehensive governance refresh often begins with a Bylaws review (ideally every three years). This isn’t about overhauling your entire system; it’s about ensuring alignment and removing inconsistencies.

Ask key questions:

- Are the committees listed in your Bylaws still active?

- Do your documents still use terms like trustee when you now say board member?

- Are quorum and term limits still appropriate?

Haldeman emphasized that this process takes time (e.g., 18 months or more) and is best done before embarking on a new strategic plan. Success requires clear communication and transparency between staff and board: sharing reports, clarifying responsibilities, and, most importantly, celebrating milestones along the way.

A Moment for Reflection and Renewal

Post-COVID governance may feel more complex, but it also offers a rare opportunity to reimagine how boards can serve our organizations more effectively. By taking stock of what we truly need from our boards and being willing to make thoughtful structural changes we can create governance systems that are not only more efficient and effective, but also more equitable and adaptive.

As Haldeman reminded us, this is the moment to adjust and prioritize—to make sure our boards are ready for what’s next.