Graduate students recently finishing an introductory course in museum management with me at George Washington University offered useful insights to the field. Their end-of-semester reflections reveal where emerging professionals are gaining traction, where they’re still uncertain, and what this means for museums and nonprofits navigating an increasingly complex landscape.

What’s clicking

A clear shift is underway in how new professionals understand museums. Rather than seeing them as a set of departments or activities, students are beginning to read museums as systems: mission, governance, finances, staffing, and programs working together—or, sometimes, at cross-purposes. Core documents like budgets, Form 990s, strategic plans, and bylaws are no longer viewed as bureaucratic paperwork, but as evidence of priorities, capacity, and risk.

Equally important, many students are learning that management is less about finding the “right” answer and more about making defensible decisions with imperfect information. That realization—often uncomfortable—is a sign of professional formation. They are also becoming more fluent in professional communication: writing memos for decision-makers, structuring findings, and using standards as tools rather than checklists.

Where the strain shows

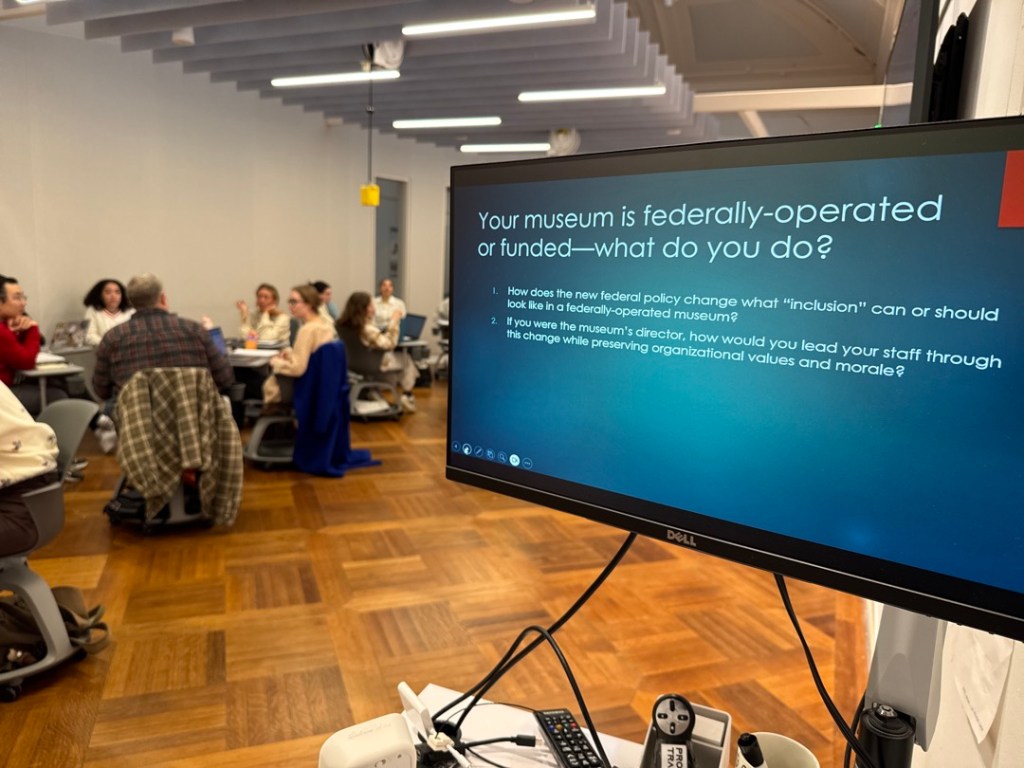

The productive strain is familiar to anyone who has worked in museums. Students struggled most when ideals collided with constraints—especially around finances, staffing, and governance. They felt the tension between mission-driven aspirations and organizational realities. That’s not a weakness; it’s the work.

More fragile, however, is the step from analysis to action. Many can diagnose issues well, but hesitate when asked to prioritize recommendations, weigh tradeoffs, or state clearly what should happen next given limited resources. Technical confidence—especially in presenting data clearly—also varies, suggesting that some skill gaps are practical rather than conceptual.

Why this matters now

For museums and nonprofits, this snapshot highlights both opportunity and risk. The opportunity lies in a generation of professionals who are learning early to think systemically, read institutions critically, and value evidence over intuition. That’s exactly what organizations need as they confront sustainability challenges, governance pressures, and heightened accountability.

The threat is a familiar one: without intentional mentoring and organizational cultures that support judgment, these emerging skills can stall. If early-career staff are shielded from budgets, planning documents, or board dynamics—or if recommendations are discouraged in favor of task execution—professional growth slows, and institutions lose potential leadership capacity.

Implications for the field

For museum managers and nonprofit leaders, the message is straightforward:

- Invite early-career staff into the real work. Where appropriate, share documents, explain tradeoffs, and talk openly about constraints. Transparency builds competence.

- Model prioritization. Show how you decide what not to do. This is often more instructive than celebrating new initiatives.

- Treat feedback as development, not evaluation. A culture that values revision and judgment over point-scoring mirrors how professional work actually happens.

- Invest in practical fluency. Small supports—templates, examples, shared language around evidence and recommendations—can dramatically improve confidence and effectiveness.

What comes next

For emerging professionals, the next step is practice: turning analysis into action, recommendations into decisions, and discomfort into judgment. For leaders, the task is to recognize that this developmental phase is not a liability but an asset—if it’s supported.

Museums and nonprofits don’t just need passion. They need people who can read systems, navigate constraints, and make thoughtful choices. The encouraging news? That capacity is already taking shape. The challenge now is whether our institutions are ready to meet it.

There are some great truths here – particularly

1.Management is less about finding the “right” answer and more about making defensible decisions with imperfect information.

2.Treat feedback as development, not evaluation. A culture that values revision and judgment over point-scoring mirrors how professional work actually happens.

Unfortunately, I’m not sure that the leaders in our field understand, accept or implement these beliefs well enough to teach emerging professionals.

LikeLike

I think this may be very true of all professions. I have two young emerging professionals in my family who are in different fields, but they are ready to examine the systems and work on solving problems. They get frustrated when they are shut out of the effort to help create solutions for the whole org. If we think about studies of how generations behave in the workforce, Gen X was similar in this strain (no surprise, they mostly raised Gen Z), in that they wanted (still want) all the information about why a certain decision was made. Gen X should be able to be the leaders that share information with the whole team and should be able to take the next step and involve the younger people in the decision making processes.

LikeLike