“My name is my identity and must not be lost,” declared abolitionist and suffragist Lucy Stone. Her words remind us that names are more than just labels. They tell stories, carry history, and hold cultural significance. They shape how we see ourselves and how others see us. The act of naming—whether giving, changing, or choosing a name—can express individuality, family ties, culture, faith, or resistance. Moreover, it is a deeply personal act, yet also public. A name declares: this is who I am.

As the United States marks the 250th anniversary of its Revolution, historic house museums have a unique opportunity to reflect on the women of their sites—especially those interpreting the nineteenth century. How were their names connected to individuals of the founding era? How important was it for women to assert ties to that legacy?

For women in the nineteenth century, marriage customarily submerged female identity under a husband’s surname. Often, that is where the trail seems to end. Yet some women found ways to hold onto their maiden or ancestral names—an intentional act of memory-keeping that linked them to Revolutionary roots and preserved family history across generations.

Doing History Through Names

Tracing names is one way of doing history. A surname, a middle name, even a repeated given name can reveal how families remembered their past and signaled their place in a community. These naming choices remind us that history is not only found in grand battles or famous documents, but also in the everyday acts of remembrance within families.

Two women from my hometown of Rockville, Maryland—a small community of only a few hundred residents in the nineteenth century—demonstrate how this worked in practice. Their stories suggest that similar examples might be discovered in hometowns across the nation.

Catharine Laura Williams Bowie (1808–1891)

Catharine Laura Williams Bowie offers a compelling case. When Catharine married Maryland jurist Richard Johns Bowie in 1833, convention dictated that she become “Mrs. Richard J. Bowie.” But by asking critical questions about her maiden name “Williams” and why she kept it as part of her name, we can uncover much more.

What does her full name reveal about family ties or ancestry?

Catharine’s full name—Catharine Laura Williams—firmly ties her to a prominent Maryland lineage. Newspaper accounts describe her as the “daughter of Gen. Otho Williams of Washington County,” reinforcing her connection to a well-known family. With no sons in the Williams family, Catharine may have carried the name forward to honor her family’s legacy.

Her father, born in 1776, was likely named after his uncle, Otho Holland Williams, a distinguished officer in the Revolutionary War remembered for his service under Nathanael Greene. Her paternal grandfather, Colonel Elie Marion Williams (1750–1822), served as a quartermaster during the war and clerk of Washington County Court, Maryland. This patriotic lineage, linked to the founding of the nation, may have held lasting personal and public significance for Catharine and her community.

How is she addressed in different sources?

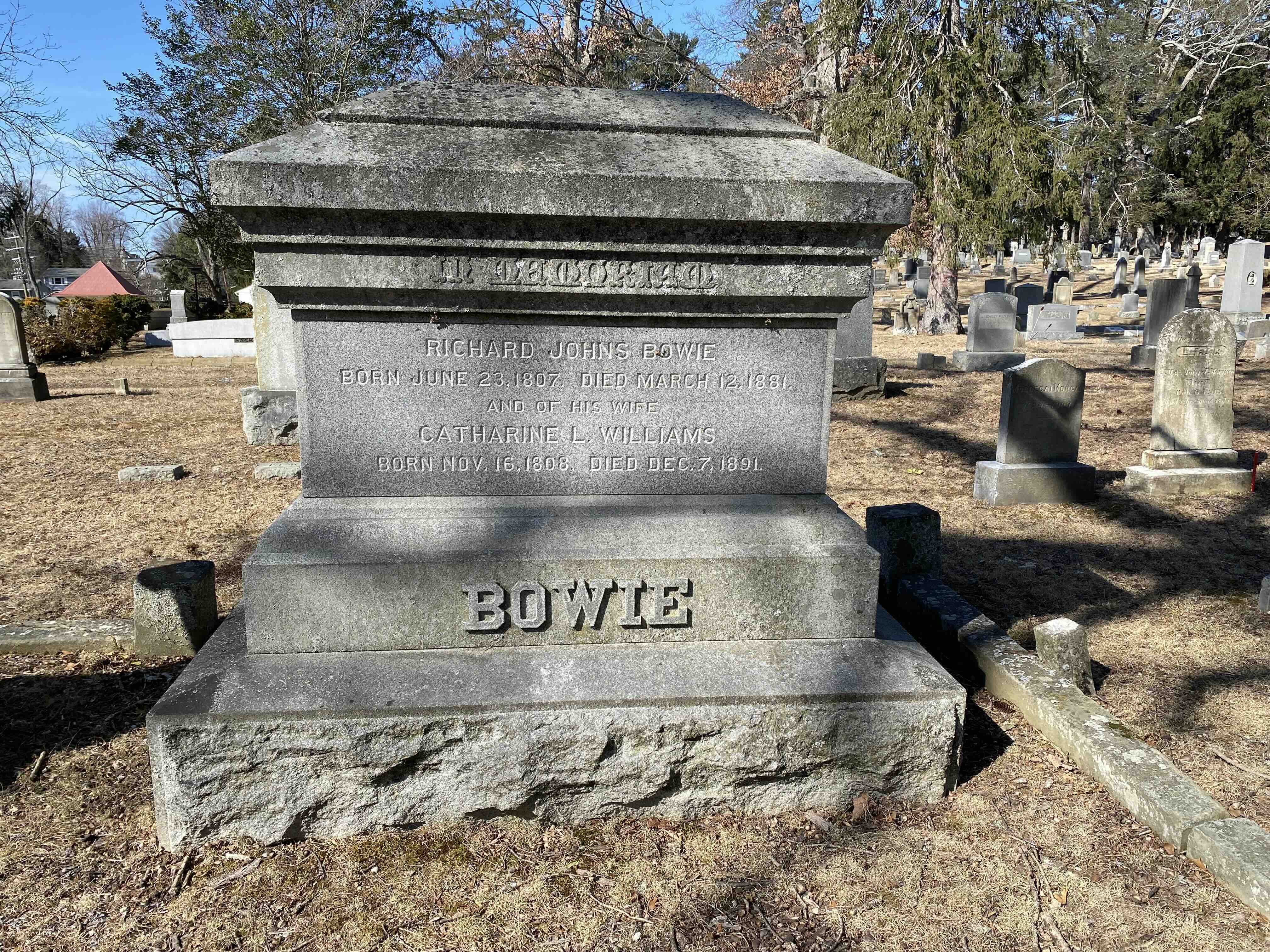

In her obituary, she is listed as “Mrs. Catharine L. Bowie, widow of the Hon. Richard Johns Bowie,” balancing her personal identity with her marital connection. Her headstone, however, lists her as “his wife Catherine L. Williams,” restoring her maiden name within the context of marriage. A smaller headstone marked “C.L.W.B.” preserves all aspects of her identity—first, middle, maiden, and married names.

Did she adopt, keep, or modify her surname after marriage?

She adopted her husband’s surname (Bowie) upon marriage, but records such as legal documents, her will, and the headstone suggest she retained and used her full name (Catharine L. Williams Bowie), indicating pride in both her birth and married families.

In a period when women’s names often vanished into their husbands’ identities, Catharine ensured her Williams lineage remained visible. Her name anchored her to a Revolutionary family and carried that memory into public view.

Rebecca Thomas Veirs (1834–1918)

Rebecca Thomas Veirs similarly demonstrates how names carried Revolutionary ties forward. The daughter of Philip Grable Biays (1797–1845) and Jane Catherine Thomas Magruder (1810–1879), she descended through her maternal line from the Hanson, Magruder, and Thomas families.

What does her full name reveal about family ties or ancestry?

Her middle name, “Thomas,” linked her directly to her maternal great-grandfather, Dr. Philip Thomas, a physician and Revolutionary leader who chaired his local committee of safety and served as an elector casting his vote for George Washington as the first president. His wife, Jane Contee Hanson, further tied the family to Maryland’s political elite and Revolutionary-era leadership. Rebecca’s use of “Thomas” preserved this lineage in her name, ensuring her connection to the founding generation remained visible.

How is she addressed in different sources?

Rebecca appears in family records, legal documents, and genealogies as “Rebecca Thomas Veirs,” balancing her married surname with her Thomas identity. In 1898, she contributed to a published genealogy documenting Revolutionary service, where her name not only authenticated her place in the lineage but also served as a public act of memory-keeping.

Did she adopt, keep, or modify her surname after marriage?

She adopted the surname Veirs after marriage, yet she retained “Thomas” as a prominent middle name throughout her life. Her children’s names—Kate Marbury, Charles, Francis Scott, Jane Biays, and James Philip Biays Veirs—extended the practice, carrying forward ancestral identities and familial ties. In this way, Rebecca used both her own name and the names of her children to preserve Revolutionary ties in the public record.

Like Catharine, Rebecca demonstrated that names were more than markers of marital status. They were carriers of memory and sustainers of historical continuity.

Why Names Matter for 2026

Why do these genealogies matter for the Semiquincentennial? Because they remind us that the Revolution was not only fought on battlefields but also memorialized in parlors, naming practices, and family histories. Women like Catharine and Rebecca ensured that Revolutionary memory endured—not through public office or published treatises, but through the lived work of sustaining kinship ties, telling stories, and recording lineages.

Doing history through names uncovers more than biographical detail. It reveals how women’s identities were shaped by, and helped shape, the Revolution’s legacy. Their names—and the names they bestowed on children—kept alive connections to ancestors who fought, organized, or endured during the nation’s founding era.

As historic sites and communities prepare for the 250th, names can serve as an interpretive key. Who in your site’s history used names to assert belonging, preserve lineage, or claim connection to the Revolution? Whose names were erased or overshadowed? How might you recover them?

By analyzing names, we widen the frame of commemoration. We see how women, too, carried the Revolution—not only in memory, but in the very names they bore, recorded, and passed on.

Tracing Her Name, Finding Her Story

When researching women in history, names offer essential clues about identity, status, and agency. Use these questions to guide deeper inquiry:

- What does her full name reveal about family ties or ancestry? Is it a family name handed down from a parent or relative?

- How is she addressed in different sources? Is she referred to by her own name (e.g., Catharine Bowie) or by her husband’s (e.g., Mrs. Richard J. Bowie)? Does this change over time?

- Did she adopt, keep, or modify her surname after marriage? What does that choice or lack of choice suggest about autonomy, cultural norms, or legal rights?

- Does her middle name carry meaning? Might it preserve maternal lineage, honor a relative, or distinguish her from others with the same first and last names?

- Does her name reflect ethnicity, immigration, or assimilation? Was it changed to fit societal expectations, and if so, what aspects of her cultural identity may have been altered or retained?

Names are not just words. They are sources and worthy of close reading and interpretation.