The Heritage Foundation’s new The Heritage Guide to Historic Sites: Rediscovering America’s Heritage promises to help Americans find “accurate” and “unbiased” history at presidential homes and national landmarks. Presented as a travel and education tool for the nation’s 250th anniversary, the site grades historic places from A to C for “accuracy” and “ideological bias.”

At first glance, it looks like a public service. But a closer look reveals that even when Heritage cites “evidence,” its historical reasoning exposes deep methodological and ideological flaws.

The Appearance of Evidence

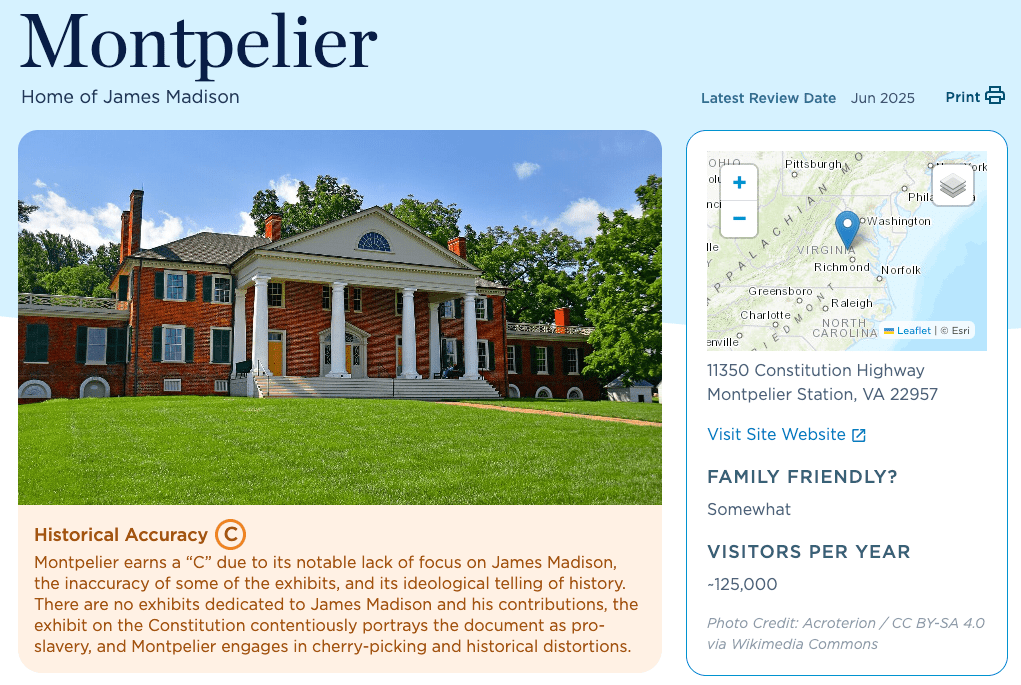

The Heritage Foundation awards James Madison’s Montpelier in Virginia a C for historical accuracy, claiming the site shows a “notable lack of focus on James Madison” and that:

- Montpelier’s exhibition on the Constitution “gives the impression that slavery was the central animating force behind the Constitution.”

- Exhibit panels “contradict Madison’s own views” and fail to note that the framers avoided the word slavery because, as Madison wrote, they “thought it wrong to admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men.”

- A display on enslaved presidents omits the fact that Washington freed enslaved people in his will.

- One panel misreports that 11% of New Hampshire’s 1790 population was enslaved (instead of 0.11%), an error first identified in 2022 but apparently not corrected.

- A short film in The Mere Distinction of Colour connects slavery’s legacy to present-day racial issues such as police brutality and Black Lives Matter, which Heritage interprets as political.

- Finally, Heritage objects to Montpelier’s 2018 “rubric” for interpreting slavery, which it portrays as “spreading an ideology” of anti-racism and “restorative justice.”

At face value, these sound like factual concerns. Yet on closer examination, they reveal the Guide’s narrow interpretive lens.

Selective Accuracy and Historical Context

One actual error—the 0.11% statistic—is fair criticism. Museums should correct mistakes promptly. But the rest of Heritage’s objections are interpretive disagreements, not demonstrations of inaccuracy.

The Guide appears to focus on Montpelier’s award-winning exhibition The Mere Distinction of Colour, which interprets the lives of enslaved people on the plantation and examines the contradiction between liberty and slavery in the early republic.

Heritage insists that the Constitution’s clauses on “domestic violence and insurrection” referred only to Shays’ Rebellion, not slave revolts. Yet scholarship on the 1787 Convention shows that delegates often discussed internal uprisings and servile insurrections in the same breath; both threatened the new republic’s stability. Historians debate the extent, not the existence, of that connection.

Heritage also treats Madison’s statement about avoiding the word slavery as evidence of moral rejection rather than political compromise—a reading many historians would consider incomplete. The Founders’ choice of the euphemism “a person legally held to service or labor,” after all, didn’t prevent the Constitution from protecting slavery through the Three-Fifths Clause (Article I, Section 2), the Fugitive Slave Clause (Article IV, Section 2), and the twenty-year moratorium on ending the transatlantic slave trade (Article I, Section 9).

Yes, President Washington freed the slaves he owned—after he and his wife had died, when they no longer needed people to work their farms. In addition, his will required that his sick and elderly slaves were to be supported—following Virginia law to prevent indigent slaves from becoming the responsibility of the state. This crucial context is missing from Heritage’s critique.

In short, Heritage presents Madison’s selective quotations as final authority and portrays any broader contextualization—about race, power, or contradiction—as “bias.” That is Heritage’s ideology disguised as neutral precision.

Importantly, the exhibition is only part of the visitor experience. The site offers guided tours of Madison’s home to share Madison’s life and legacy; operates the Center for the Constitution; and educates thousands of teachers, police officers, and civic leaders about constitutional principles every year. In other words, there is in fact a notable focus on James Madison and the Constitution—if the reviewer had taken a better look around. Again, the larger context is missing in the Guide.

It seems that Heritage downgraded Montpelier not because it misrepresents Madison, but because it also interprets the enslaved community. The reviewer seems to have evaluated the exhibitions, not the tours or programs that most visitors experience—and ignored substantial examples of balanced, evidence-based interpretation.

Misunderstanding Museum Practice

Heritage’s complaint about the film linking slavery’s legacy to modern racial issues also betrays a misunderstanding of how museums work. Public historians regularly connect historical themes to present-day questions to help audiences find relevance and continuity—one of the field’s best practices in civic education. As Shakespeare observed, “what’s past is prologue.” The past and present are connected and the job of the historian is to make the links visible.

Similarly, the best practices on interpreting slavery that Heritage dismisses as “ideological” was developed with the National Trust for Historic Preservation and a wide range of scholars, museum professionals, and Montpelier descendants. It has been widely adopted for ethical reasons: it involves people in the interpretation of their own ancestors’ lives. Calling this “spreading ideology” mischaracterizes a professional standard for inclusion and accountability.

The Professional Standard: Transparency and Balance

According to the American Historical Association’s Standards of Professional Conduct, historians must present evidence honestly, cite sources, and recognize complexity. Heritage’s Guide does none of this. It quotes selectively, offers no references, and presumes a single correct interpretation of Madison’s intentions.

Heritage’s grading system punishes exactly the practices that organizations like the American Alliance of Museums, American Association for State and Local History, American Historical Association, and National Council on Public History recommend.

Pedagogical Poverty

From the perspective of L. Dee Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning, Heritage’s approach also misses the mark. The Guide values only “Foundational Knowledge”—names, dates, and quotations—while ignoring other essential dimensions of learning:

- Integration: connecting ideas like liberty and slavery.

- Human Dimension: understanding the experiences of enslaved people and their descendants.

- Caring: motivating civic reflection and moral engagement.

- Learning How to Learn: encouraging visitors to question, compare, and evaluate evidence.

Museums like Montpelier intentionally design experiences that nurture these dimensions. Heritage’s “grading” system penalizes them for doing so.

Good history invites visitors to question, connect, and reflect. Heritage’s approach instead tells them to trust its verdicts and avoid sites that challenge them.

Why This Matters

The Historic Sites Guide arrives as museums prepare for the 250th anniversary of American independence. In today’s polarized climate, Heritage’s letter grades offer an easy shorthand: patriotic sites get A’s; those that interpret race, women, or power get C’s.

Heritage’s entry on Montpelier shows how “accuracy” can be reduced to the selective defense of one historical narrative. The organization’s critique, though sprinkled with facts, ultimately rejects the pluralism, transparency, and civic engagement that define best practices in public history—and the values I support for America as well.

For museum professionals, the lesson is clear: maintain high standards of evidence, acknowledge complexity, and keep history connected to the present.

This is a great analysis! Thanks so much!!Gretchen

LikeLike