The fundamental boundaries of historic preservation have been significantly expanded by San Francisco Heritage, one of the country’s leading historic preservation organizations. In Sustaining San Francisco’s Living History: Strategies for Conserving Cultural Heritage Assets, they state that, “Despite their effectiveness in conserving architectural resources, traditional historic preservation protections are often ill-suited to address the challenges facing cultural heritage assets. . . Historic designation is not always feasible or appropriate, nor does it protect against rent increases, evictions, challenges with leadership succession, and other factors that threaten longtime institutions.” In an effort to conserve San Francisco’s non-architectural heritage, historic preservation must consider “both tangible and intangible [elements] that help define the beliefs, customs, and practices of a particular community.” Did you notice the expanded definition? Here it is again: “Tangible elements may include a community’s land, buildings, public spaces, or artwork [the traditional domain of historic preservation], while intangible elements may include organizations and institutions, businesses, cultural activities and events, and even people [the unexplored territory].”

With many historic preservation organizations, it’s all about the architecture so protecting landscapes, public spaces, and artwork is already a stretch. They’re often not aware that landscape preservation goes back at least a generation. It was a new idea in the 1950s when the Accokeek Foundation preserved the view across the Potomac River from George Washington’s Mt. Vernon, but today it’s a familiar domain for historic preservation (although not always practiced). Redefining historic preservation to include organizations, businesses, activities, and people will be difficult, but it also isn’t a new idea. It has been codified in the international preservation field beginning with the Burra Charter in 1988 and thoughtfully explored in Place, Race, and Story: Essays on the Past and Future of Historic Preservation by Ned Kaufman in 2009. San Francisco Heritage is taking these academic and global ideas and applying them to their own community, and as we know, San Francisco is experiencing skyrocketing land prices that are forcing everyone but the wealthy out of town. Although architecture may be preserved, it’s seriously eroding historical, social, and cultural fabric of the community.

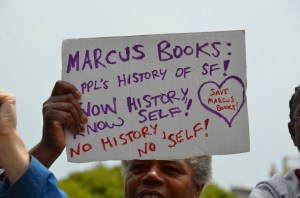

Supporters of Marcus Books rally to save the historic business, a cornerstone of San Francisco’s African American community. Photo by Steve Rhodes/Flickr.

Some may feel this work is beyond the responsibility of historic preservation, but I continue to be concerned that preservation’s primary mantra is based on economics and finances. Historic preservation and heritage tourism do play an important role in economic revitalization, but it’s not the only role. Indeed, there are many reasons to preserve history. Tom Mayes, deputy general counsel at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, recently shared his personal reflections on the value of old places, including learning, creativity, sacredness, design, history, beauty, identity, memory, continuity, and sustainability. Many of these values can be just as easily applied to organizations, businesses, activities, and people as they can to architecture and landscape, so why shouldn’t our thinking about historic preservation be holistic and ecumenical as well?

Next week preservationists around the country will meet in Savannah, Georgia for the National Preservation Conference and it’ll be interesting to see how they respond. By their nature, preservationists are continually pulled in many directions–tradition and innovation, commercialization and interpretation–and my sense is that lately they’ve been more concerned with economic sustainability than culture and history. They may find Sustaining San Francisco’s Living History to be irrelevant, inappropriate, or innovative, but I’m hoping it’s the latter.

To learn about the public reaction to Sustaining San Francisco’s Living History, see

- San Francisco Chronicle: “Taking Care of Business in SF’s High Turnover Climate” (10/12/14) This is the second front-page story on the legislation in as many weeks.

- KRON News: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C3nwQXsNOgo. Although San Francisco Heritage is not mentioned specifically, this is a really great story. The reporter, Vicki Liviakas, unfolds Heritage’s Legacy “pocket guide” in the studio!

- KGO News: http://abc7news.com/politics/new-legislation-is-trying-to-protect-old-businesses-/349367/. Mike Buhler, executive director of San Francisco Heritage, is interviewed.

- San Francisco Examiner: “SF to explore registry program to assist longtime businesses with rising rents“

- Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation: This blog reviews Heritage’s recent policy paper, “Sustaining San Francisco’s Living History”: http://gvshp.org/blog/2014/10/10/ideas-for-preserving-our-small-businesses-and-creative-spaces/. Their Facebook post states: “Some New Yorkers dismiss San Francisco as a small town, but SF has serious ideas to share about how every city can keep its character in the face of rampant development.”