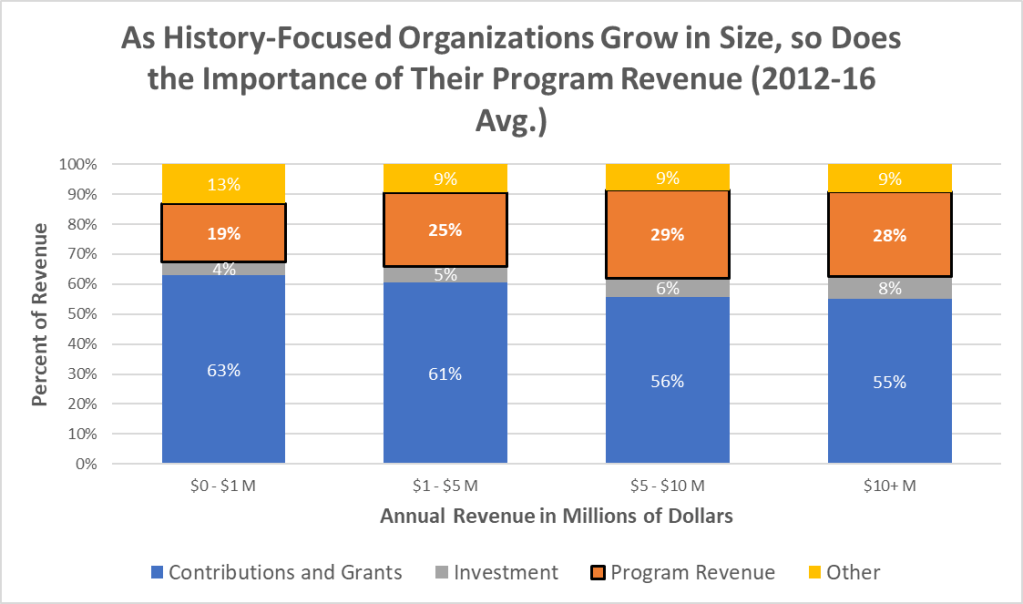

For small non-profit organizations operating on less than a million dollars annually, programs are often the beating heart of the operation. The best programs balance mission and financial sustainability to serve their audiences. Program revenue (admissions, events, and membership dues) can be a vital means of maintaining financial stability and growth. For History-Focused Organizations [Museums (NTEE A50), History Museums (A54), History Organizations (A80), and Historical Societies & Historic Preservation (A82)] as overall revenue grows, so does the share of program revenue. This means as your organization grows, so should the prominence of your programs as a true revenue driver (see figure 1 below).

As small history-focused organizations expand, it’s crucial to manage their programs wisely to increase income while keeping the mission in mind. For small groups, program decisions can be very personal, often influenced by board or staff interests. Taking a strategic approach to these decisions can boost the organization’s growth and success.

Who Is Your Audience?

For small history-focused organizations, community engagement is a key aspect of successful programming. Programs that deeply engage local audiences can spark frequent attendance. This can include hosting educational workshops, offering free or reduced admission days, partnering with local schools and community groups, and featuring local artists or historical artifacts. Fostering a sense of community ownership not only drives attendance but also generates revenue through program fees and membership sales.

Start thinking about who your audiences are through the lens of demographics, geography, and lifestyle. Who are your biggest and most supportive audiences? What is the potential for growth? Remember, you can’t serve everyone perfectly all at once, especially with limited resources. Consider which audience segments can benefit from your current strengths and abilities. Then, identify which skills or expertise should be enhanced or prioritized to cater to your target audience more effectively. Once this is done it is easier to carve out your unique niche within your ecosystem and avoid exhausting resources trying to out-compete others.

Forming partnerships with local schools, community groups, and subject matter experts can significantly enhance the allure and impact of the museum’s programs. These collaborations allow for resource sharing, knowledge exchange, and the crafting of programs that capture a wider audience’s interest. These cooperative ventures can foster a sense of communal identity, creating a robust network of support and engagement among all involved parties. Drawing on Michael Porter’s competitive strategy theory, these strategic partnerships can give museums a competitive advantage, allowing them to differentiate their offerings without needing to develop new competencies in-house.

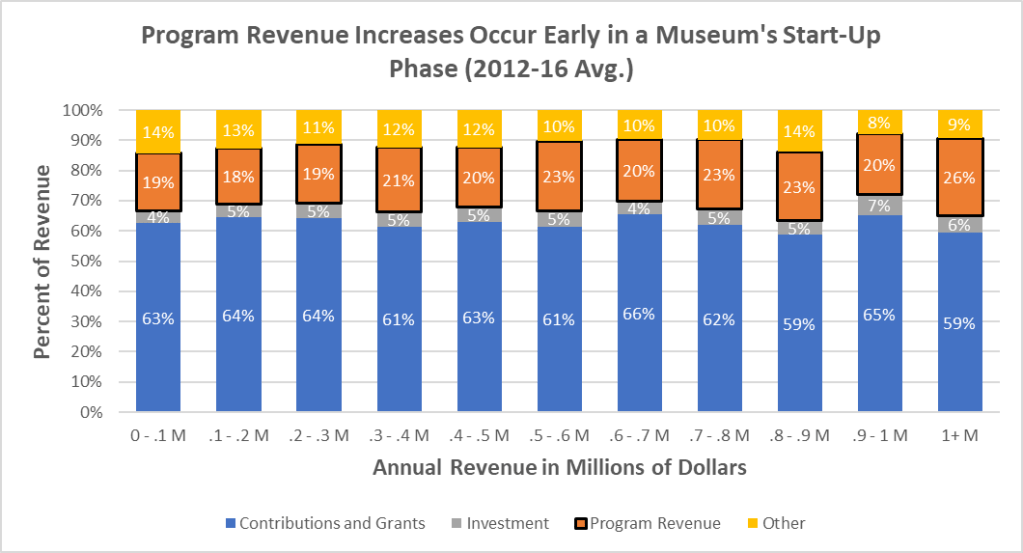

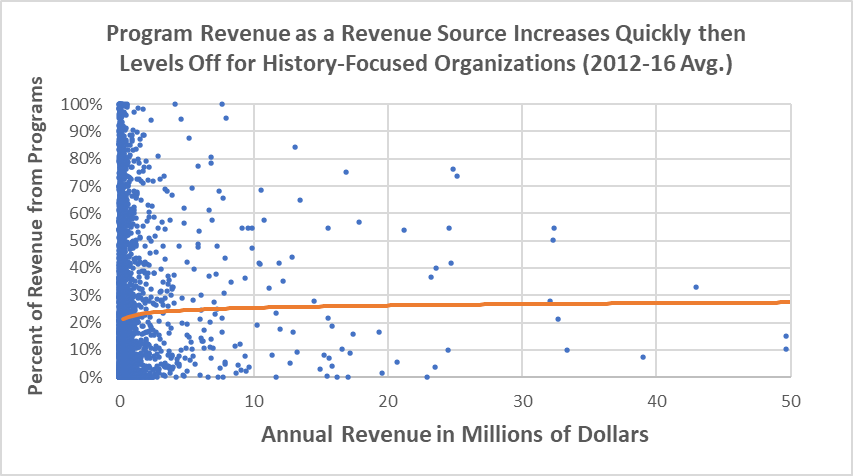

The capacity to establish and grow programs that both generate revenue and align with the mission is a key indicator of organizational maturity. In figure 2 above, notice that the percentage of program revenue increases as the organization’s total revenue increases. But this growth seems to be short-lived. In Figure 3, each dot represents a history-focused organization. The dot’s position is determined by the size of the museum and the proportion of their revenue derived from programs. The orange trendline summarizes these individual data points, illustrating a swift rise in programs as a significant source of revenue. However, this growth slows as organizations approach $2 million in revenue.

Program Revenue Means Maturity (Maybe)

Within the realm of small, history-centric institutions, the potential expansion of program revenues might best be interpreted through the lens of Susan Kenny Stevens’ lifecycle theory for nonprofits. This conceptual framework suggests that as organizations transform from mere concepts into established institutions, they go through distinct phases characterized by escalating capacity which is defined by Stevens as ”organizational capability and competence.” As Stevens puts it, “programs, management, governance, financial resources, and systems — will look quite different stage to stage.”

As history-focused organizations transition from “start-up” into the “growth” phase, they may witness a significant expansion in program revenue. This growth often goes hand-in-hand with the improvement of organizational systems and the development of more professional work procedures.

However, as these institutions progress towards a “maturity” phase, the exponential growth in program revenue often begins to stabilize, as other revenue streams gradually consolidate and serve as reliable pillars of financial support. Yet, this plateau should not be mistaken for stagnation. Stevens’ theory suggests “once a healthy organization reaches maturity, the need to maintain its competitive edge and vibrancy requires continual strategic program additions and deletions. In this way, mature organizations oscillate between growth and maturity to stay vibrant.” Hence, in order to remain vibrant, mature organizations continuously balance growth and maturity through strategic program iteration.

In extending Stevens’ lifecycle theory, it’s essential to note that some history-focused organizations may not significantly depend on program revenue, even when they reach the “maturity” phase. This deviation from the expected pattern can be attributed to the unique nature of their funding structure or revenue model. Of course this doesn’t mean that these organizations have no programs or visitation, they just don’t seek to generate revenue from them. Refer back to figure 3, there is incredible diversity in the portion of revenue that comes from programs.

Such organizations might rely heavily on alternative sources of income, such as grants, endowments, or donations. These alternative revenue streams often come to serve as the organization’s primary financial backbone. While this might seem to deviate from the anticipated lifecycle progression, it may simply be a reflection of the organization’s specific context and business model and does not necessarily indicate a deficiency of strategic management. This is the situation for the Knights of Columbus Museum in New Haven, Connecticut which operates on more than $2 million in revenue each year, zero percent of which comes from programs. This organization is driven by a strong sense of charitable giving paired with many free mission-based programs. While flexing their programming muscles, they’ve decided it is not within their principles of unity and charity to charge for programming.

Building on Stevens’ lifecycle theory, the focus of an organization’s approach to programming should be strategic and comprehensive, rather than purely revenue-driven. Rather than viewing programming solely as a source of income, organizations must recognize it as a vital part of their mission and services, integral to achieving their objectives and serving their community. This holistic approach requires a well-planned and strategic program development process. By aligning their programming efforts with their overall mission and values, organizations can ensure their initiatives are not just financially sustainable, but also resonant and impactful within their community.

Stick to the Plan

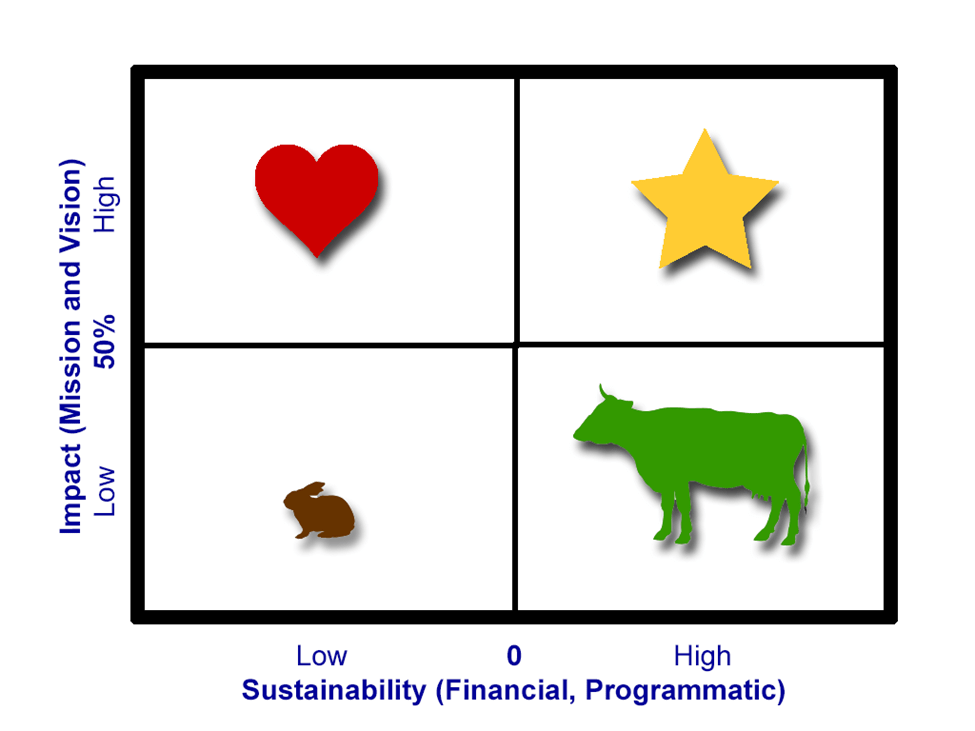

One way to help direct thinking when it comes to program priorities is through the Impact-Sustainability Matrix. This tool can analyze existing programs to help make decisions toward greater impact and sustainability. Aligning this matrix with the thinking of Michael Porter, a business strategy professor at Harvard Business School, can help assemble a roster of programs that further your institution

Most programs can fit into four categories:

- Stars: Advance mission and vision and are sustainable

- Hearts: Advance mission and vision and are not sustainable

- Cash Cows: Unrelated to mission and vision and are sustainable

- Rabbits: Unrelated to mission and vision and are not sustainable

In the context of strategic planning our Rabbits, Cows, Hearts, and Stars constitute the crucial pillars of our business plan. Rabbits are a drain on your organization and should be eliminated or evolved to improve their impact and/or sustainability. Consider the perception of value, you could begin charging for a free program to make it more financially viable and express its value to your audience base. Could the program be repurposed to align better with your mission and vision while keeping its current structure? If neither of these changes are feasible, eliminate the rabbit to make way for a more sustainable or impactful program.

Cows, on the other hand, align with Porter’s emphasis on the economic value chain. Even though they may not be directly impactful to mission and vision, their financial contribution bolsters a museum’s stability, and their existence in a business plan ensures the financial resources required for other, more ambitious initiatives.

Hearts encapsulate Porter’s notion of differentiation, helping an organization stand out in a competitive landscape. These programs, while demanding more resources, align closely with mission and vision and can cement identity in the eyes of the audience. The challenge for an organization, as reflected in our business plan, is to effectively manage these programs to ensure they don’t compromise financial stability.

Stars represent the ideal blend of Porter’s competitive strategies—differentiation and cost leadership. These programs align deeply with our specific mission while also proving economically sustainable. In any history-focused organization business plan, the goal is to cultivate more ‘Stars’, as they embody the perfect equilibrium between fulfilling mission and ensuring long-term viability.

Applying Porter’s strategic lens to programming categories can help craft a comprehensive business plan—one that effectively balances mission fulfillment, financial stability, and competitive advantage while setting the stage for long-term success and growth of history-focused organizations. Remember, even mature organizations can benefit from this framework as they seek to remain vibrant through continual strategic reevaluation of their programs.

In summary, the growth and success of small history-focused organizations are deeply tied to their ability to create engaging, distinct programs that not only resonate with their audience but also generate sustainable revenue. As these organizations grow, it’s essential that they strategically leverage their resources, partnerships, and community ties to continually refine and expand their offerings. By doing so, they create an ecosystem of mutual support and engagement, while driving the organization’s financial stability and mission fulfillment. Our next post will focus on the strangest and broadest revenue stream of history-focused organizations known ambiguously as “other”.

References

Stevens, Susan K. Nonprofit Lifecycles: Stage-Based Wisdom for Nonprofit Capacity. Stagewise Enterprises, 2008.

Magretta, Joan. Understanding Michael Porter: The Essential Guide to Competition and Strategy. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2012.

I know this is a bit late, but I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that the first break point ($0-$1million) for small museums creates a category that makes all further analysis moot. The generally accepted budget size for small museums is under $350,000, and many are much smaller than that. While there may be some growth in these organizations over time, a jump of one or more million is highly unlikely.

LikeLike