During my recent visit to several London museums, I was struck by the growing emphasis on decolonization. As a museum professional, I’ve been following this movement for some time, but seeing these efforts firsthand inspired me to reflect on the challenges and progress being made. Some London museums are actively re-examining their collections and narratives, working to address the complex legacies of colonialism in tangible ways, and both Royal Collections and the National Trust have staff members specifically focused on this issue. But others have a long way to go.

If you’re not familiar with decolonization, it’s the process of rethinking and revising interpretations that have historically favored the perspective of a dominant power, such as an imperial empire over a colonized nation (like Great Britain and India). However, decolonization goes beyond the empire-colony dynamic, addressing any situation where one perspective is elevated due to power imbalances. For instance, terms like “prehistory” suggest a time without history, labeling settlers as “pioneers” overlooks the people who were already living in those areas, and describing conquering armies bringing “civilization” implies they were superior to the existing cultures. Words shape our perceptions and carry significant consequences, influencing relationships across race, gender, and other social divides. Decolonization helps us recognize and correct these biases, leading to more inclusive and accurate narratives.

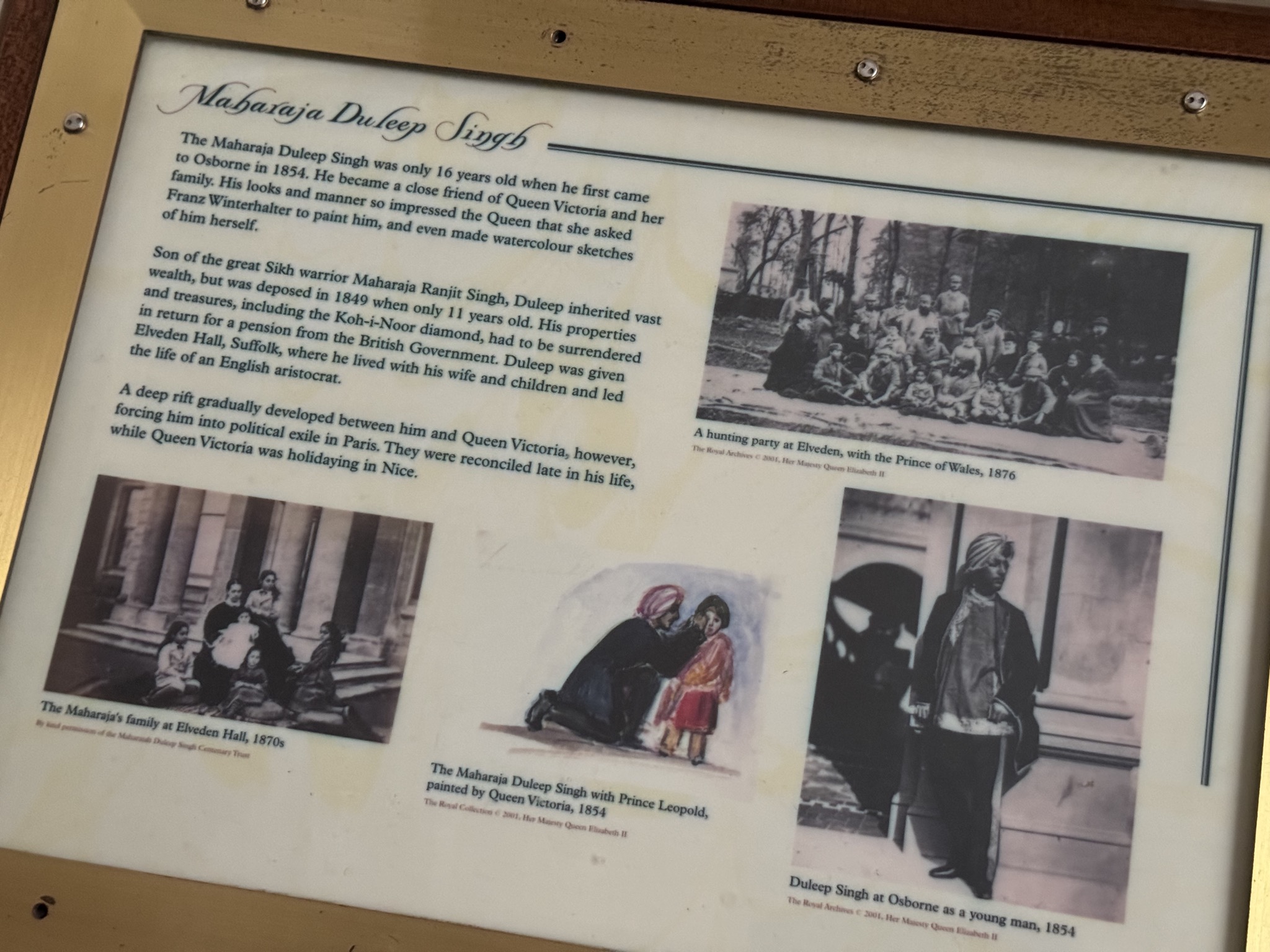

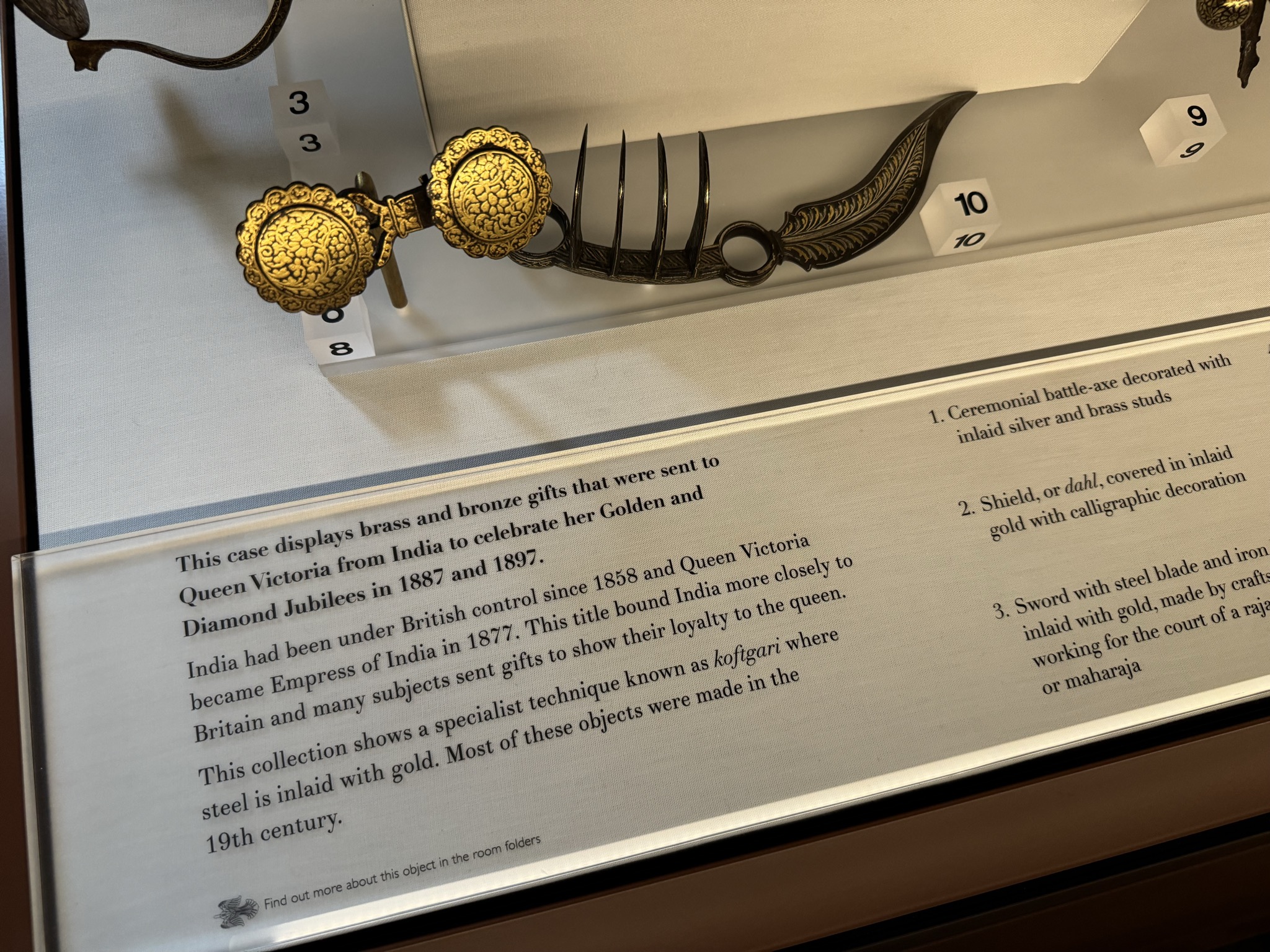

For an example of a museum waiting to undertake a re-examination of its exhibitions, consider Osborne House (operated by English Heritage), the country palace of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. The displays in and around the Durbar Room discuss Britain’s relationship with India. The exhibitions include a panel about Maharaja Duleep Singh and that “his properties and treasures, including the Koh-i-Noor diamond, had to be surrendered in return for a pension from the British Government” and feature gifts sent from India to Queen Victoria to “show their loyalty to the queen.” The history is far more complex and this exhibition emphasizes only the British perspective and continues a mythology of India’s grateful subservience to the Queen.

1. Re-examining Collections

Many London museums are conducting in-depth reviews of their collections to identify items acquired during the colonial era. This process includes acknowledging the contexts in which objects were collected, often under unequal power dynamics. They are being more transparent about the provenance of key objects but contested ownership isn’t addressed publicly. Some examples:

Natural History Museum: a notice about colonialism and efforts to “take a detailed look at our collection and our history in order to tell the full story of the origins of the Museum and the people represented in it.”

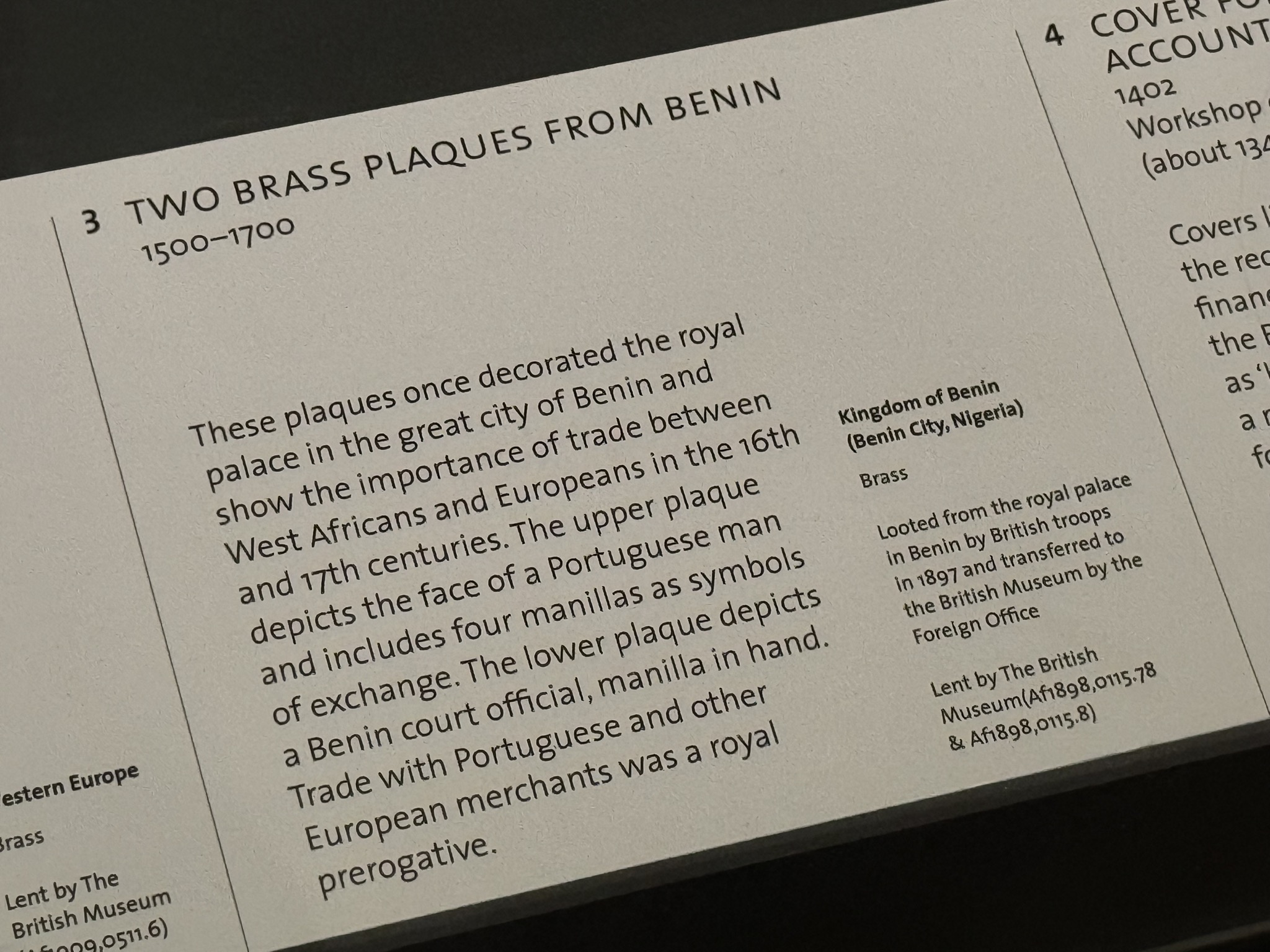

Victoria and Albert Museum: exhibition label for two brass plaques “looted from the royal palace in Benin by British troops.”

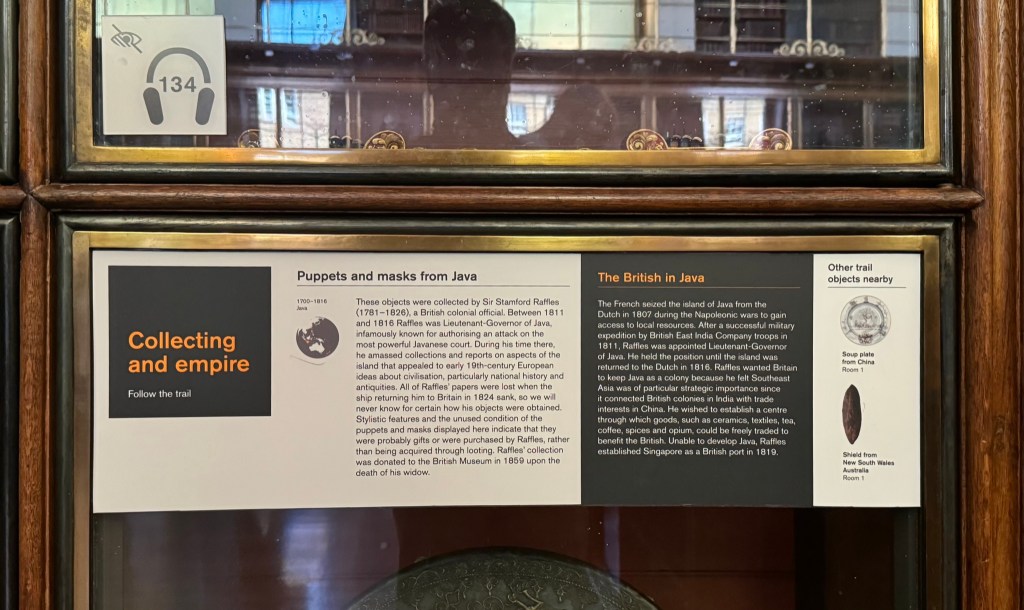

British Library: “Treasures” exhibition label for historic Javanese manuscripts “acquired after an attack by British forces in June 1812.”

2. Inclusive Storytelling

A core component of decolonization is revisiting the narratives presented in exhibitions. Museums are shifting from Eurocentric perspectives to more inclusive storytelling, incorporating the voices and histories of the cultures from which the objects originated. For example:

British Museum: Interpretive labels added to existing “Enlightenment” exhibition.

Hampton Court Palace (operated by Historic Royal Palaces): exhibition label in “The Tudor World” listing the impact of the Tudors, including the “colonisation of Ireland” and “global ambitions for an empire,” encouraging visitors to question assumptions.

3. Restitution and Repatriation

Discussions around the restitution and repatriation of artifacts have gained momentum. According to the Guardian, London museums are lagging behind their regional peers in returning objects to their countries of origin. Repatriation is not a simple process; it requires careful negotiation, cultural sensitivity, and legal considerations as we’ve discovered with NAGPRA in the United States.

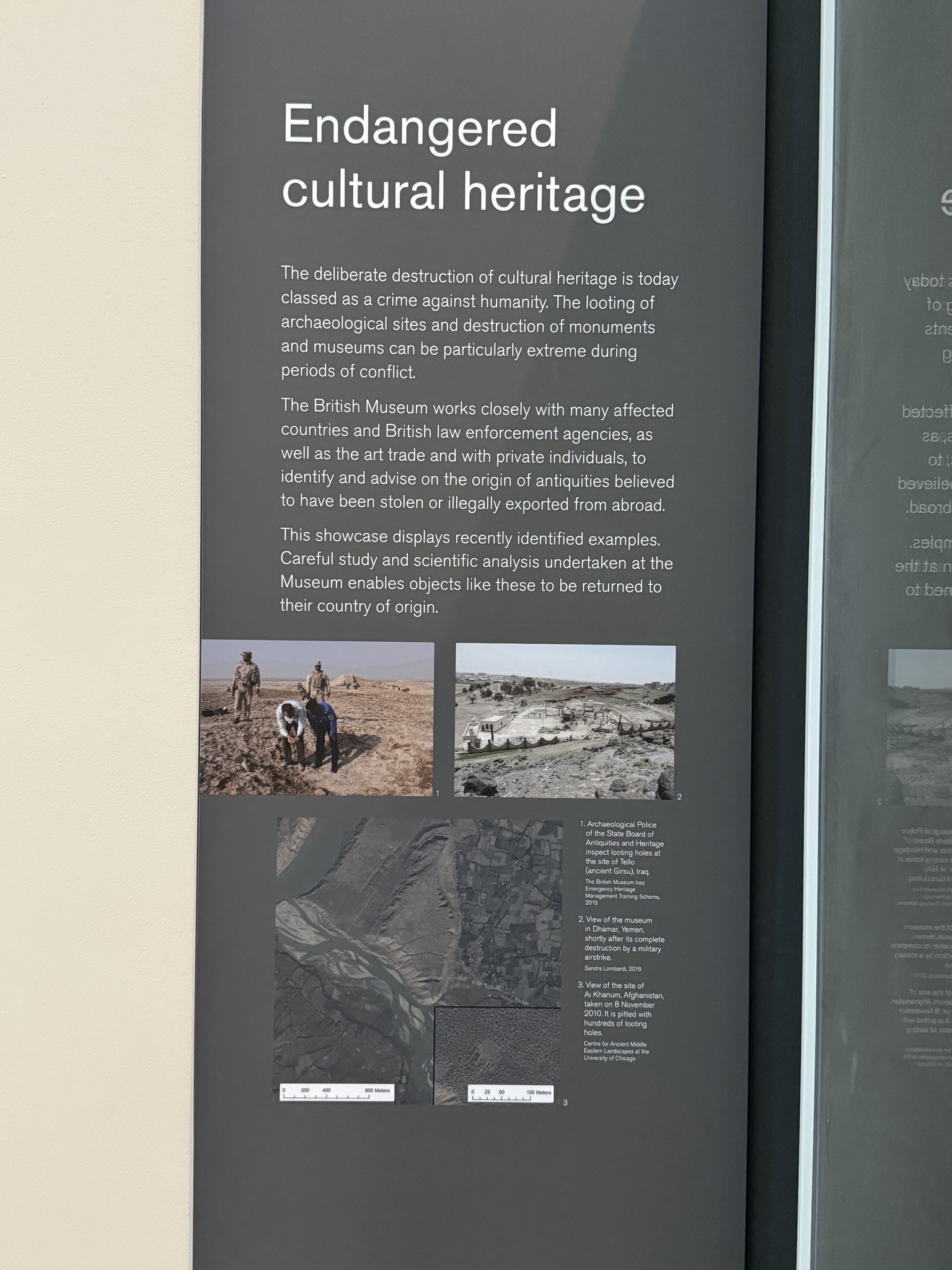

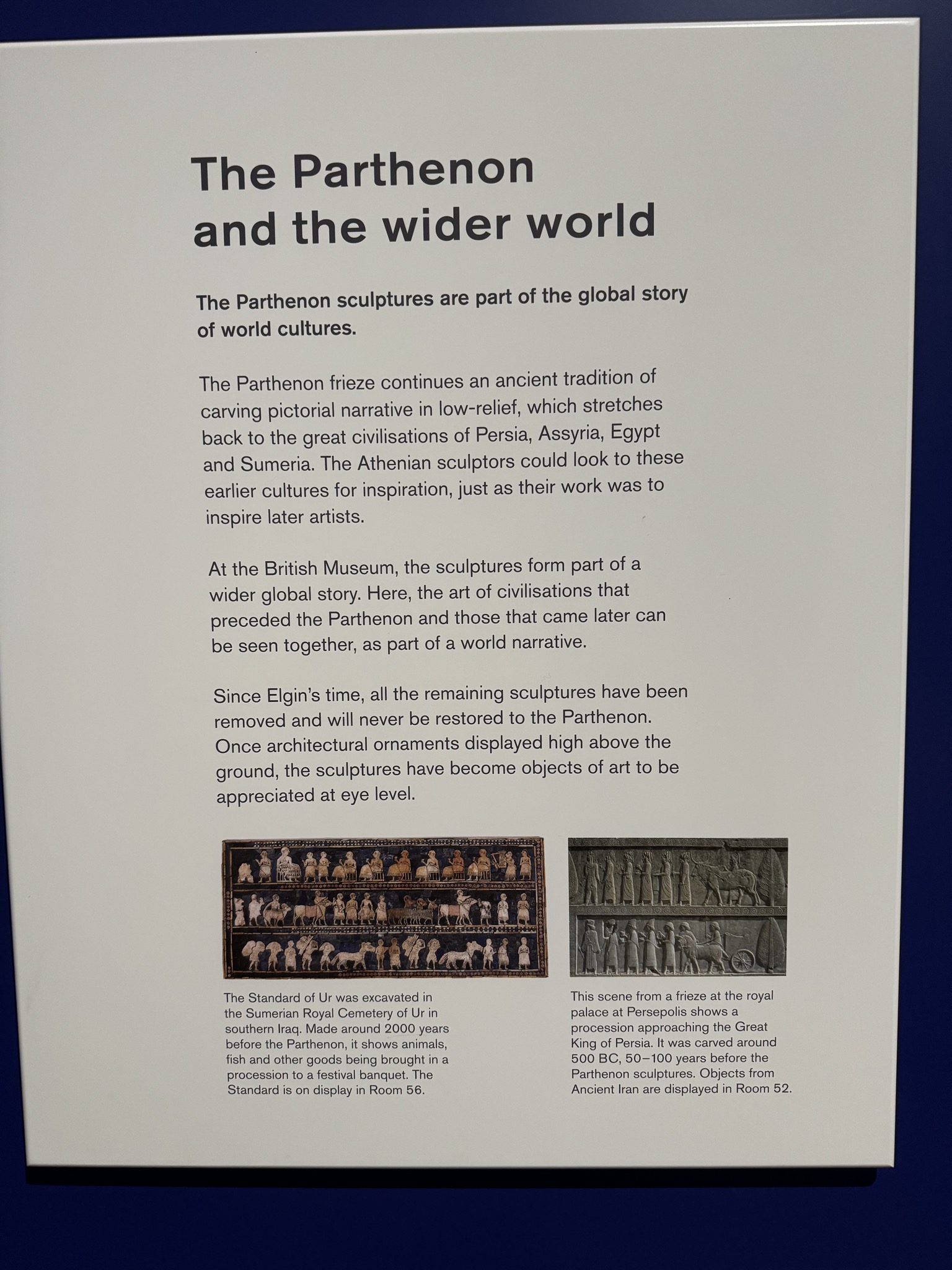

It can also cause an organization to be of two minds at the same time. At the British Museum, one exhibition will discuss the museum’s efforts to prevent theft of cultural materials in other countries, whereas the status of the infamous Parthenon Sculptures is less (and online, there’s a different description of repatriation efforts). It might be due to the silos that exist in large institutions or it could be that national museums are subject to Parliament’s policies.

Moving Forward

I didn’t see exhibitions based on collaboration with communities, especially those directly impacted by colonial histories nor evidence of management change, such as governance structures, staff diversity, and institutional policies. That may be happening behind the scenes and omitted from exhibitions. Nevertheless, the current status of decolonization in London museums reminds me of the framework Jennifer Eichstedt and Stephen Small developed for interpreting slavery in Representations of Slavery: Race and Ideology in Southern Plantation Museums. It seems they’re moving in a range from “symbolic annihilation” to “trivialization and deflection” to “segregation and marginalization.” What I didn’t encounter is “relative incorporation,” the most inclusive approach where the experiences and perspectives of every community involved is incorporated into the broader interpretation—but I’m hoping that’s the next step in the process.

Decolonization in museums is an ongoing journey rather than a finite project. It requires sustained effort, reflexivity, and a willingness to embrace complex and sometimes uncomfortable truths about the past. Many London museums are moving forward in this work, but it is a collective endeavor that requires the participation and support of museum professionals worldwide. By sharing experiences, strategies, and challenges, museums can learn from one another and continue to move toward more equitable and inclusive practices.

For museum professionals, this journey involves not only transforming how history is presented but also reshaping the museum as an institution that acknowledges and acts upon its responsibilities in an evolving world. If you are interested in learning more, follow these links:

- “Coloniality and the British Museums” by Toby Ahamed-Barke, History Workshop, February 22, 2024.

- “Decolonizing Britain: An Exchange,” Twentieth Century British History, 33 no. 2 (June 2022), https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hwac018

- The Museum of British Colonialism