Imagine this: you’ve spent weeks planning a concert at your local history museum. You’ve arranged every detail, from booking a fantastic band to setting up the stage. The chairs are perfectly aligned, the lighting is just right, and the atmosphere feels full of possibility. But as the start time approaches, your excitement gives way to nervous glances at the clock. The parking lot remains empty. You keep hoping someone will arrive late, but after ten minutes, the seats are still vacant. The band—thankfully understanding—decides to use the time to practice, and while their music fills the room, you’re left grappling with embarrassment and frustration. Just a week earlier, a similar concert you organized thirty miles away had a packed house. What went wrong this time? How could the results be so different?

That happened to me early in my museum career and it was a humbling lesson. Perhaps you’ve faced similar moments—community events that fell flat, partnerships that fizzled, or publicity that didn’t attract attention. It’s easy to feel defeated when a community group declines to collaborate because their priorities don’t align, or when a business association’s objectives clash with the mission of interpreting artifacts rather than hosting public events. Sometimes, the problem is simply bandwidth—not enough staff to attend community meetings or follow up with volunteers. Community engagement can feel like a puzzle with a lot of missing pieces. But with the right tools, those challenges can transform into opportunities.

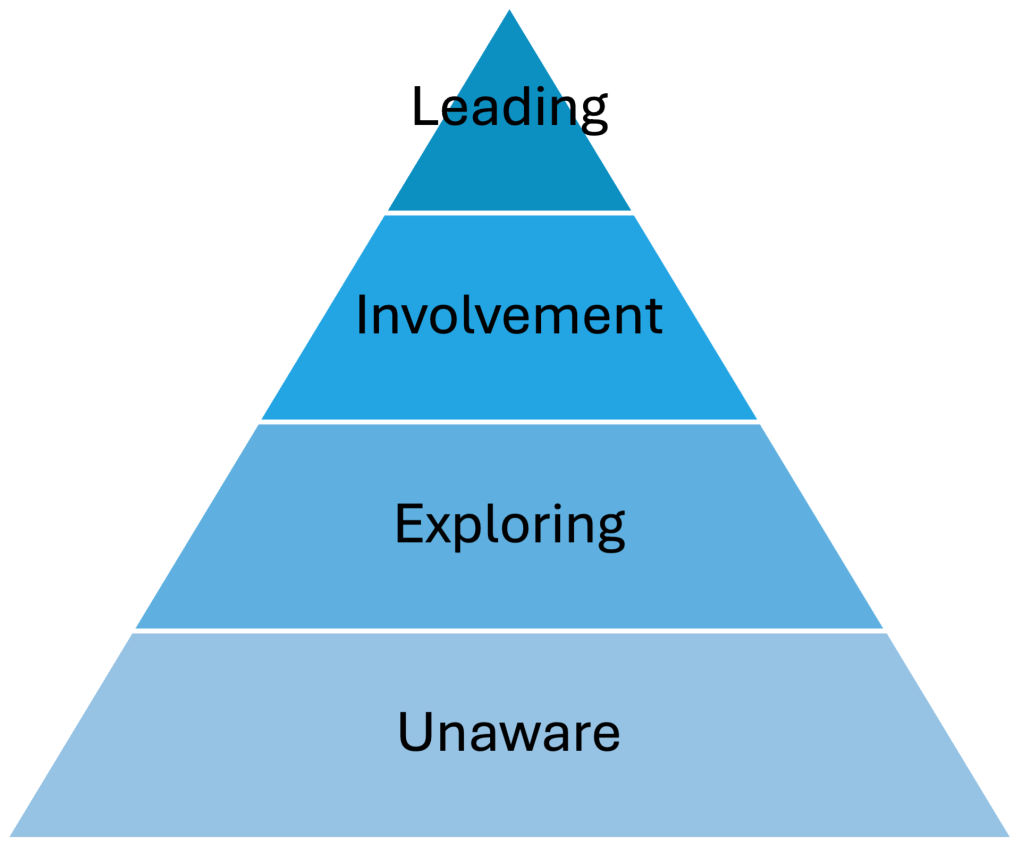

The Engaging Places Pyramid is one such tool that can make a big difference. Informed by the latest research and long-tested theories, it offers a clear process for connecting with audiences at different levels—from disinterested community members to dedicated advocates. It simplifies community engagement into four distinct stages: unaware, exploring, involvement, and leading. This article provides an overview of the Pyramid and walks through its steps with practical examples to demonstrate how it works in action.

The Pyramid not only helps align activities with your museum’s mission, but it also informs decisions about programs and experiences that resonate with your community, no matter their level of involvement. The goal isn’t just to bring people in the door but to build long-term connections that matter. Whether you’re just starting or looking to deepen your engagement efforts, the Engagement Pyramid can help museums of any size create meaningful relationships with the people they serve—and build organizational capacity.

A Brief History of the Engagement Pyramid

Fifty years ago, psychologists Irwin Altman and Dalmas Taylor noted that relationships grow gradually, moving from surface-level interactions to deeper, more meaningful connections.[1] This concept suggests that museums must engage visitors through increasingly deeper, mutually beneficial connections—from initial awareness to active leadership. By taking incremental steps to build trust and engagement, museums can ensure that relationships evolve naturally and sustainably over time.

Those incremental steps began to be defined by Sherry Arnstein in the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. In 1969, she published the intentionally provocative “Ladder of Citizen Participation,” which became a foundational concept for community engagement in city planning and local government.[2] Her ladder included three major rungs—non-participation, tokenism, and citizen control—which were further divided into eight minor steps (see figure 1). Many organizations have adopted this framework to evaluate the depth and quality of engagement efforts. It highlights the critical role of power dynamics, emphasizing that meaningful engagement means giving people both a voice and the power to make decisions.

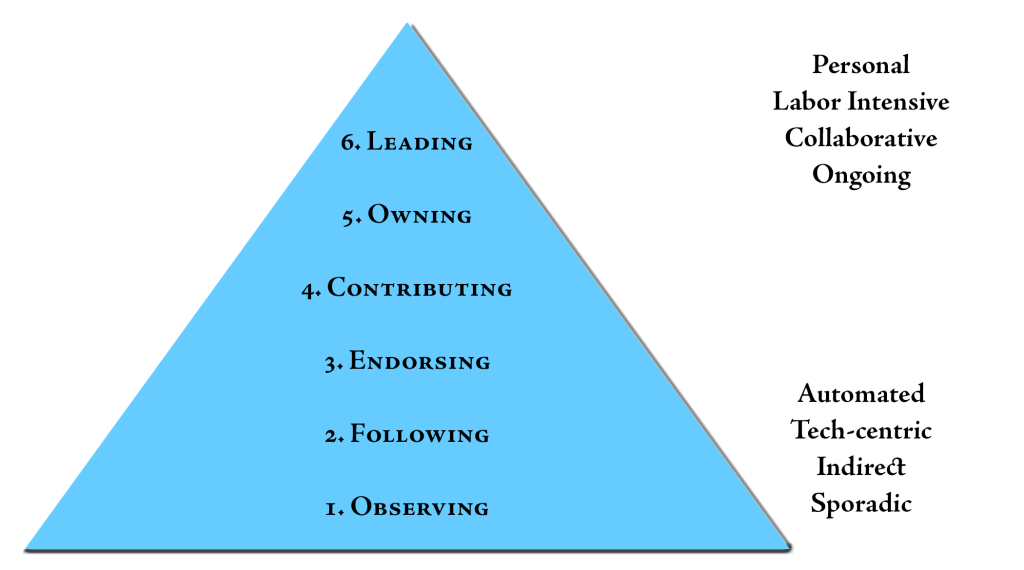

Both of these ideas received a major rethinking in the early 21st century as a result of the growth of the internet and social media. Around 2006, the consultants at Groundwire developed an Engagement Pyramid, a six-level framework to help environmental organizations build better strategies for engaging people (see figure 2). They believed that civic engagement builds power—power that influences decisions shaping society and impacting the planet. At the heart of their approach is the Engagement Pyramid, a framework informed by community organizing, relationship marketing, and fundraising principles.

Groundwire’s pyramid illustrates how engagement narrows from many observers at the base to a smaller group of contributors and even fewer leaders at the top. This structure is similar to the donor pyramid used in fundraising but incorporates technology-driven and personal interactions to maximize outreach and deepen connections. At the lower levels, tools like websites, email, and social media are essential for automating interactions and reaching large audiences efficiently. This approach ensures foundational engagement can scale effectively to include broad audiences with minimal effort.

As engagement intensifies toward the upper levels of the pyramid, personal connections become increasingly important. While digital tools remain useful for managing routine communications, they are less effective in cultivating the deep, meaningful relationships needed at higher levels of engagement. Here, human interaction—through one-on-one conversations, personalized outreach, and tailored experiences—becomes essential for fostering commitment and advocacy.

Together, these frameworks provide a foundation for understanding the evolution of engagement strategies, from theoretical underpinnings to actionable steps—but much more has been learned in the last twenty years.

The Engaging Places Pyramid: A Four-Level Model for Museum and Community Connections

Unlike previous models, the Engaging Places Pyramid directly address the interests of public historians, such making history accessible, participatory, and relevant. It adopts Altman and Taylor’s theory and adapts key principles from Groundwire’s and Arnstein’s frameworks while incorporating more recent research on engagement in museums and historic sites.[3] The result is a framework that can be tailored to different situations and that reflects both the public’s level of interest and the museum’s approach to fostering deeper connections (see figure 3).

The Engaging Places Pyramid simplifies community engagement into four distinct stages, which is much easier for public historians to adopt and follow:

- Unaware: At this stage, individuals are not aware of the museum or do not see it as relevant to their interests. They may have visited in the past but see no current reason to engage. Communications should focus on increasing visibility and demonstrating relevance through marketing and public relations efforts.

- Exploring: Here, individuals have developed a mild interest in the museum’s mission and activities. They might follow its social media accounts, subscribe to newsletters, or attend occasional events. Engagement at this level should prioritize building trust and providing information through accessible channels like email campaigns or social media updates. For example, a visitor who subscribes to a newsletter (Exploring) might be encouraged to attend an exclusive event, deepening their connection and moving them into the Involvement stage.

- Involvement: At this stage, individuals begin to actively support the museum. They might contribute financially, volunteer, or participate in specific programs and events. Personal invitations, event coordination, and direct outreach become critical for deepening involvement. This is the level that is traditionally considered “community engagement,” but is difficult to achieve without addressing the previous two stages.

- Leading: This is the highest level of engagement, where individuals are fully committed to the museum’s mission and success. They take on leadership roles, advocate for the museum in their communities, and contribute significant resources, such as requesting funding at a city council meeting. Communication at this level is highly personal and requires sustained, meaningful relationships. This can also be a period of hesitation for the museum because its mission, vision, values, and practices may be actively debated and questioned.

Public historians can use these stages to design tailored and intentional strategies that build stronger connections with their communities. This approach not only helps bring more people into the museum but also transforms them into lifelong supporters and advocates. Are there exceptions to this engagement process? Absolutely. The public may begin engagement at any level, and practitioners may have developed a different engagement model with additional layers or nuances. While no single framework can fully capture the complexities of community engagement, the Engaging Places Pyramid serves as a conceptual map—a starting point to visualize the process and navigate its challenges.

I’m currently working with Ken Turino on a book on community engagement, which will describe the Pyramid in more detail as well as provide examples of the theory in action through multiple case studies. If you would like suggest your museum, historic site, or historical society as a case study, let us know at ken.turino@gmail.com or max.vanbalgooy@engagingplaces.net.

References

[1] Dalmas Taylor and Irwin Altman, “Communication in Interpersonal Relationships: Social Penetration Processes,” in Interpersonal Processes, edited by Michael Roloff and Gerald Miller (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1987), 259+.

[2] Arnstein, Sherry R. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35, no. 4 (1969): 216-224.

[3] It also incorporates other influential thinkers, such as Steven Blank, Ash Maurya, and Jim Kalbach on customer engagement; marketing insights from Philip Kotler, Neil Kotler, and Wendy Kotler; and organizational lifecycle frameworks by Ichak Adizes and Susan Kenney Stevens.