The Jenrette Foundation’s State of American Historic Preservation Education (September 2025) lands like a wake-up call for our field. At more than 25 pages, it’s not just a summary of trends in preservation education—it’s a challenge to rethink what we mean by “historic preservation” altogether. Although the report focuses on universities and training programs, its insights are strikingly relevant for leaders at historic sites and house museums.

At its core, the report argues that historic preservation is due for a rebranding—not a new slogan, but a new mindset. “Preservation isn’t about old buildings,” the authors write, “it’s about shared futures.” That’s a phrase that will resonate with anyone who’s struggled to convince visitors, funders, or policymakers that historic sites matter. For years, preservationists have known that saving a place is just the start; what matters is how that place connects to people, stories, and community life. The Jenrette report gives that idea institutional weight, calling for preservation to be seen as a civic, cultural, and economic force—an engine for workforce development, sustainability, and belonging.

The report’s emphasis on storytelling, collaboration, and interdisciplinary thinking matches the daily realities of site directors who balance history with hospitality, education, and revenue. Its critique of elitism and nostalgia also mirrors the conversations many of us are having about interpretation—whose stories are told, who feels welcome, and how our work contributes to justice and climate resilience.

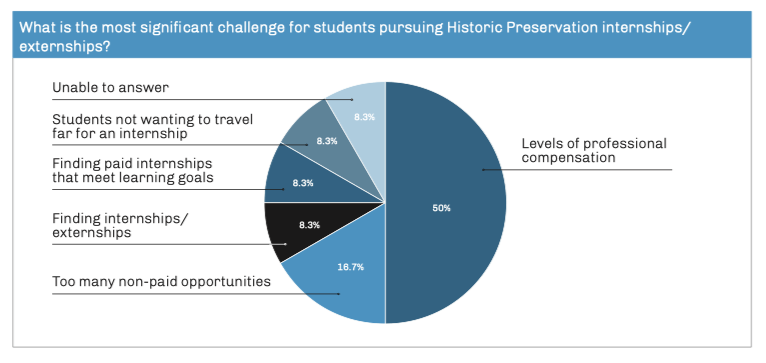

But the report goes further, urging preservationists to embrace the skills and partnerships that make these ideals sustainable. It recommends closer ties between education and practice—hands-on training, internships, and community-engaged projects that produce professionals who are both thinkers and doers. For historic sites, that’s an invitation to host students, share expertise, and become living classrooms for preservation’s next generation. It also suggests a way to solve one of the field’s persistent challenges: attracting new, diverse talent. If students see historic sites as places of innovation and relevance—not just repositories of the past—they’re more likely to stay in the field.

The report’s economic argument will also sound familiar to site leaders who’ve learned to connect preservation with local vitality. It notes that preservation generates jobs, strengthens small businesses, and fuels cultural tourism—all themes that make our work easier to explain to city councils, chambers of commerce, and donors. Reframing preservation as infrastructure for community resilience could help historic sites position themselves as indispensable civic assets rather than optional cultural luxuries.

The Jenrette report’s most compelling message may be its insistence on humility and openness. Preservation, it argues, must become porous—welcoming new ideas, disciplines, and audiences. That’s a useful reminder for all of us managing historic places: our future depends not on what we’ve saved, but on how we invite others to join the work.

If there are weaknesses in the report it’s an inadequate discussion of methodology and a lack of evidence for their conclusions. It’s unclear who participated in the May 2025 survey or in the June 2025 convening. Was it all academics, as the Foundation’s Historic Preservation Education Advisory Committee is currently composed, or did it include other stakeholders, such as recent graduates of historic preservation programs and the organizations that hire them (e.g., historic sites, house museums, government agencies). The absence of voices from employers, mid-career professionals, and recent graduates weakens claims about “the field” writ large. The report sometimes implies national consensus but it may actually reflect a small subset of university professors.

Despite its weaknesses, the report serves a useful purpose: it articulates the direction preservation education ought to move. It’s a vision document, not a white paper. For leaders at historic sites and house museums, the key is to treat it as an agenda to test, not as settled evidence. The next step should be collaborative research—surveys that include employers, alumni, tradespeople, and community partners—to validate or challenge its claims.

What do you think? Does “historic preservation” generate objections over elitism and nostalgia in your community? How can smaller sites build partnerships with universities or preservation programs to strengthen hands-on learning? What’s one change that could make graduate education more relevant to the realities of your work?