One of the things I keep returning to in my teaching and consulting is how much museum work actually lives along a spectrum—not in binary terms of success or failure, right or wrong, compliant or noncompliant.

This is one of the persistent challenges of working with professional standards. Standards are essential. They articulate shared values, define public trust, and help the field hold itself accountable. But by their nature, standards can imply an all-or-nothing logic: either you are doing the thing or you are not. And if you are not, that’s a problem.

Museum management, of course, is far more complex.

Museums and historic sites operate with widely varying levels of capacity, expertise, staffing, governance maturity, and external pressure. Boards change. Funding fluctuates. Crises intervene. Even within a single organization, some areas of work may be highly developed while others lag behind—not because of neglect or incompetence, but because of constrained resources and competing priorities.

Over time, I’ve become interested in how we might better describe and normalize that reality for the field—without lowering expectations or abandoning standards altogether.

Why a Matrix (Not a Scorecard)

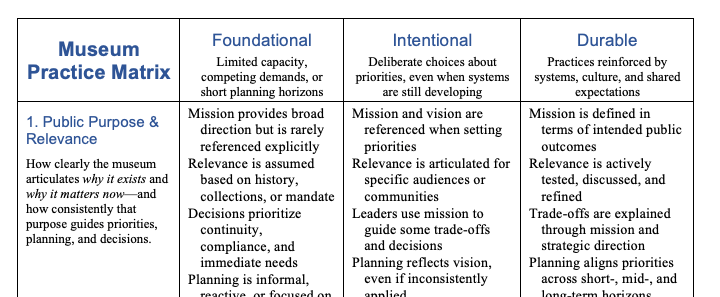

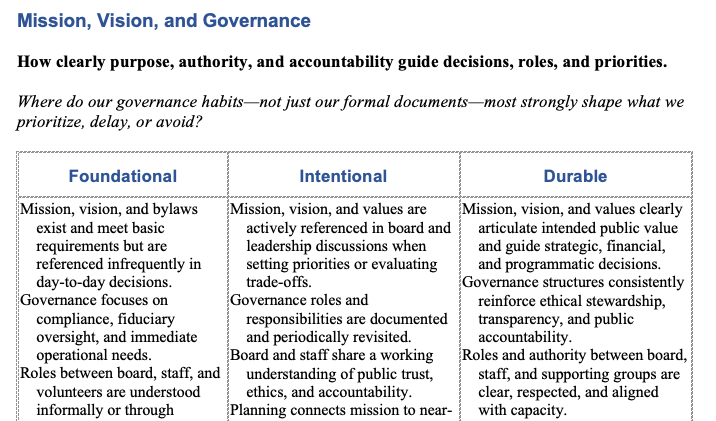

In different contexts, I’ve heard similar tools described as rubrics, spectrums, continuums, or maturity models. In my own work, I’ve settled on calling this a matrix, for a very specific reason: it allows us to look across multiple areas of practice at once.

Once you do that, patterns start to emerge.

You may see that your museum is quite intentional about interpretation but still operating in a more foundational way when it comes to management systems. Or that community relationships are strong, but learning and evaluation are underdeveloped. Or that stewardship practices are solid, but public purpose and relevance are not consistently guiding decisions.

That kind of insight is difficult to get from a checklist.

A matrix doesn’t tell you whether you are “good” or “bad.” Instead, it helps you see how you tend to operate under current conditions—and where greater intentionality or stronger systems might have the greatest payoff.

Capacity, Context, and Professional Judgment

This matters particularly for mid-career museum professionals.

At this stage, many people feel pulled in multiple directions at once. There are always more opportunities than time. You may feel pressure to adopt new practices, respond to emerging expectations, or fix areas that have been underdeveloped for years. At the same time, burnout is real, and capacity is finite.

One of the most common questions I hear—sometimes explicitly, sometimes implicitly—is: Am I focusing on the right things right now?

A matrix is not an evaluation tool. It’s closer to a diagnostic instrument—something you can use on your own, with your leadership team, or with your board to support higher-level conversations:

- Where are we operating mostly on individual effort rather than shared systems?

- Where are our aspirations outrunning our capacity?

- Where might modest investments—or clearer priorities—make a meaningful difference?

Importantly, being in a particular column is not a judgment of commitment or quality. Foundational practices are often entirely appropriate given an organization’s size, resources, or moment in time. The problem is not where you are—it’s not being clear about why you’re there, and what that enables or constrains.

Testing the Idea in Practice

For an upcoming leadership and strategy workshop for mid-career museum professionals that I’m co-leading with Ken Turino, I pulled these ideas together into a draft Museum Practice Matrix. It’s based not only on theories and practices promoted by leaders in the museum field (e.g., Stephen Weil, Randi Korn, and Rebekah Beaulieu), but also from innovative management thinkers (e.g., Peter Senge, David Peter Stroh, Clay Christensen, Bob Willard). The goal was to give participants a way to step back from individual projects and look across major areas of museum work—public purpose, organizational culture, community relationships, learning and adaptation, stewardship, and management—and ask, “Where are we now, really? And where might it make sense to go next?”

The matrix reflects different ways museums operate under varying conditions of capacity and context. Most organizations occupy multiple columns at once. That’s normal. In fact, that’s the point.

At this stage, I see the matrix as provisional—something to introduce, test, and refine through use. I’m less interested in perfect language than in whether it helps museum professionals think more clearly and compassionately about their work.

A Conversation with STEPS

As we were developing this tool, Ken and I inevitably found ourselves talking about the Standards and Excellence Program for History Organizations (STEPS) from the American Association for State and Local History. We’re both longtime members of AASLH and are currently co-leading workshops on reimagining historic sites and house museums for them (next up: Nashville!).

STEPS is, fundamentally, a rubric. And it’s a good one—carefully constructed, field-tested, and deeply grounded in professional practice. Our question wasn’t whether STEPS is valuable (it is), but how this matrix-based way of thinking might relate to it.

What emerged is not a replacement, but a companion.

The matrix doesn’t address every STEPS area in detail. Instead, it synthesizes major concepts into patterns of practice that tend to appear as capacity develops. It asks a different—but complementary—question:

- STEPS asks: Which standards are we meeting?

- The matrix asks: How do we tend to operate, and what does that enable or constrain?

Used together, I think the two tools can reinforce each other. The matrix can help organizations avoid jumping too quickly to tactics or checklists and instead focus on strengthening the underlying practices that make progress through STEPS more effective and sustainable.

An Open Invitation

I’m sharing this work not because I think it’s finished, but because I think it’s worth discussing. Last fall, I integrated STEPS into all of my museum studies courses at the George Washington University, from museum management to community engagement, with great success. Students gained a much clearer sense of how to apply the AAM Standards as well as develop more thoughtful recommendations. Next, I’ll add the Companion to test its value with emerging professionals.

Would a tool like this have been helpful if you were just beginning STEPS? Is it more useful as an introduction, a companion, or a standalone reflection exercise? Are there areas of practice that feel missing or underdeveloped in this first draft?

If you’re interested, I’d love to hear what resonates, what doesn’t, and how you might adapt something like this for your own organization or teaching. Feel free to leave a comment below—or contact me directly.

This is, after all, an experiment in helping our field move from activity to intention, and from judgment to professional judgment.