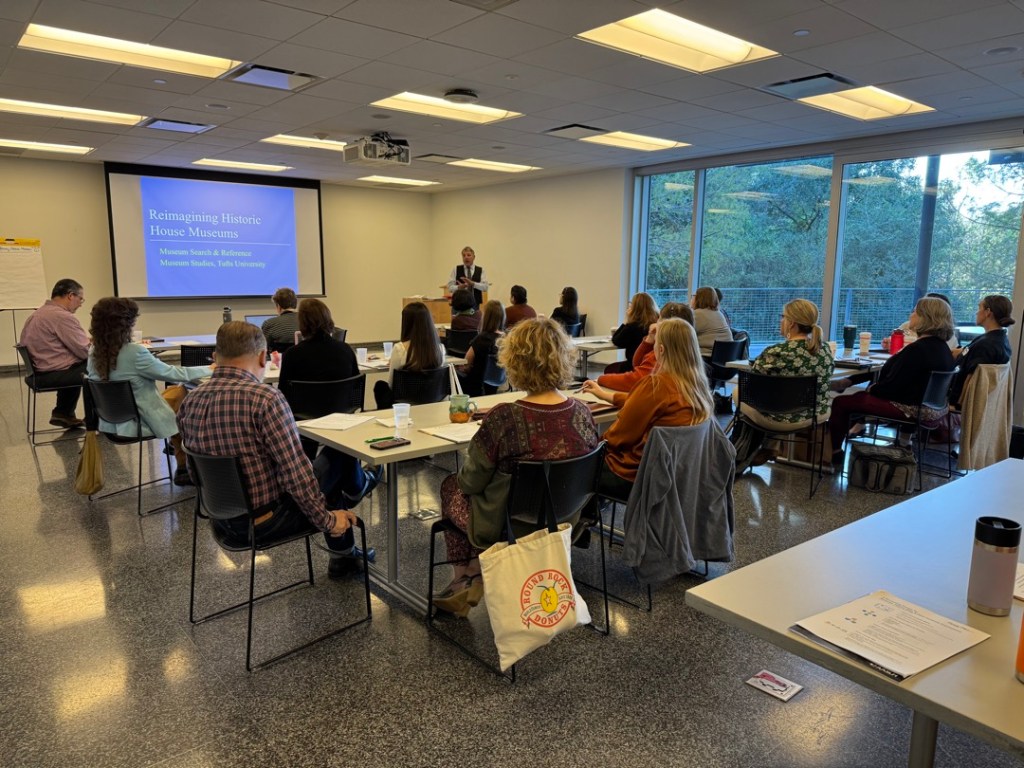

In July, Ken Turino and I will be leading the one-day Reimagining the Historic House Museum workshop on Friday, July 10, 2026, at Belle Meade Historic Site & Winery in Nashville, Tennessee. It’s designed specifically for people working at house museums and historic sites who are wrestling with familiar questions: How do we refresh our programs? Attract new audiences? And build a more sustainable future without losing what makes our site special? Registration is $225 for AASLH members and $350 for nonmembers.

The day combines current social and economic research with practical tools drawn from nonprofit management and business strategy. Participants conduct a holistic assessment of public programs, explore examples of sites that are successfully reinventing themselves, and take part in a facilitated brainstorming session that puts new ideas into practice using a real house museum as a case study.

Continue reading