Rowman and Littlefield, publishers for AASLH and now AAM, are offering a 35% discount on most of their titles through September, including both print and ebooks. That includes the Interpreting series, which was recently joined by Interpreting Naval History by Benjamin Hruska and Interpreting Difficult History by Julia Rose (Julie will be sharing a panel with me at the AASLH meeting in Detroit) and by the end of the year it’ll have ten titles. Other areas of interest are museum studies, architecture and historic preservation, and museum administration. Browse their web site at Rowman.com and use the code 16SUMSALE when you order online or by phone at 1-800-462-6420. The sale will continue to be in effect during the AASLH annual meeting in September, so you’ll want to be sure to stop by the Rowman and Littlefield booth to look at what’s available. On Thursday, September 15 from 3-4 pm, several authors will be available to chat and sign books (including me) and they’ll be providing coupons for deep discounts on forthcoming books.

Rowman and Littlefield, publishers for AASLH and now AAM, are offering a 35% discount on most of their titles through September, including both print and ebooks. That includes the Interpreting series, which was recently joined by Interpreting Naval History by Benjamin Hruska and Interpreting Difficult History by Julia Rose (Julie will be sharing a panel with me at the AASLH meeting in Detroit) and by the end of the year it’ll have ten titles. Other areas of interest are museum studies, architecture and historic preservation, and museum administration. Browse their web site at Rowman.com and use the code 16SUMSALE when you order online or by phone at 1-800-462-6420. The sale will continue to be in effect during the AASLH annual meeting in September, so you’ll want to be sure to stop by the Rowman and Littlefield booth to look at what’s available. On Thursday, September 15 from 3-4 pm, several authors will be available to chat and sign books (including me) and they’ll be providing coupons for deep discounts on forthcoming books.

Category Archives: Historic preservation

IMHO: Historic Preservation Needs to Move the Goal Posts

One way to measure the success of historic preservation is to count the number of listings on the National Register of Historic Places. In its first year nearly 700 properties were registered, and today the National Register has more than 90,000 entries representing nearly 1.8 million buildings, sites, and structures and is growing at a rate of about 1,500 listings annually. We could easily celebrate that as an achievement of the National Historic Preservation Act, however, the sobering truth is that fewer and fewer Americans find historic sites “inspirational” or “beneficial,” to use NHPA parlance. In the last thirty years, the number of adults who visited an historic park, monument, building, or neighborhood has dropped, from 39 percent in 1982 to 24 percent in 2012. A similar pattern appears in a study of cultural travelers in San Francisco, which showed that while 66 percent said that historic sites were important to visit, only 26 percent had actually visited one in the previous three years.

One way to measure the success of historic preservation is to count the number of listings on the National Register of Historic Places. In its first year nearly 700 properties were registered, and today the National Register has more than 90,000 entries representing nearly 1.8 million buildings, sites, and structures and is growing at a rate of about 1,500 listings annually. We could easily celebrate that as an achievement of the National Historic Preservation Act, however, the sobering truth is that fewer and fewer Americans find historic sites “inspirational” or “beneficial,” to use NHPA parlance. In the last thirty years, the number of adults who visited an historic park, monument, building, or neighborhood has dropped, from 39 percent in 1982 to 24 percent in 2012. A similar pattern appears in a study of cultural travelers in San Francisco, which showed that while 66 percent said that historic sites were important to visit, only 26 percent had actually visited one in the previous three years.

There are probably several reasons for this decline, including the near-elimination of history from public schools and a decreasing amount of leisure time, but our own field of historic preservation may also be at fault. Over the past fifty years, historic preservation has become more complex, often requiring expertise in legal strategies, real estate development, fundraising, and architectural conservation. It’s become more focused around technique, such as how to designate a property, navigate Section 106, or repair a double-hung window. It’s become more intellectual, with battles fought over statements of significance, National Register criteria, and applicability of the National Environmental Policy Act. It’s become an endless circuit in which we seem to fight the same battles and hear the same objections: “We can’t save everything,” “It’s not historic,” “We can’t stop progress,” and “You’re taking away my rights.” Historic preservation seems to have become less, rather than more, relevant and meaningful to Americans since the passage of the NHPA.

Maybe we’ve confused the ends with the means and are chasing the wrong goals. Preservation is not a destination but a means of reaching a destination. So what is the goal of preservation? According to the NHPA, it’s a “sense of orientation” and a “genuine opportunity to appreciate and enjoy the rich heritage of our Nation.” We need to rebalance the term “historic preservation” so that there’s equal emphasis on both words, rather than just the latter. We need to move the goal posts so that historic preservation is not about something but for somebody.

As management guru Peter Drucker reminds us, the nonprofit organization’s “product is a changed human being. Non-profit institutions are human-change agents. The ‘product’ is a cured patient, a child that learns, a young man or woman grown into a self-respecting adults, a changed human life altogether.” Historic preservation is not just about saving buildings; it’s about changing the lives of people.

Protecting, preserving, and interpreting is not sufficient. These are simply methods, tasks, jobs, works, or actions that define a purpose and explain how it will be accomplished. What is needed is a goal, a destination, a target, an idealized description of the future that explains “why.” To borrow from grammar, we need Continue reading

Challenges Facing Historic House Museums: A Report from the Field

At the annual AASLH workshop on historic house museum management, we always start by asking participants about the biggest or most important challenge they are facing at their historic site. For the participants, the exercise allows them to get to know each other beyond a name by recognizing the issues they may have in common. As the instructors, It’s an opportunity for George McDaniel and me to ensure we address their concerns. For AASLH, it’s a way of keeping a finger on the pulse on what’s happening in the field. At the end of the workshop, we review the list and provide some time for participants to develop a plan to address their issue. As a reminder, they also fill out self-addressed postcards with a message to themselves, which I’ll mail to them in six months.

So that you can keep your finger on the pulse of the field, here’s the list of issues and challenges from the Cedar Rapids workshop at Brucemore, which included participants from Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Illinois: Continue reading

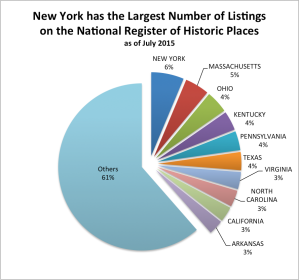

New York Tops the National Register of Historic Places

Whether it’s New York State or New York City, they’re at the top of the list in the National Register of Historic Places, the official list of the Nation’s historic places worthy of preservation. The State of New York has 5,774 properties and the City of New York has 766 listed on the National Register as of July 2015, the latest information available from the National Park Service. More than 90,000 properties have been added to the Register since it was established by Congress in 1966 (yes, next year is its fiftieth anniversary).

Whether it’s New York State or New York City, they’re at the top of the list in the National Register of Historic Places, the official list of the Nation’s historic places worthy of preservation. The State of New York has 5,774 properties and the City of New York has 766 listed on the National Register as of July 2015, the latest information available from the National Park Service. More than 90,000 properties have been added to the Register since it was established by Congress in 1966 (yes, next year is its fiftieth anniversary).

We might have some fun with the National Register and misuse it to identify the most historic cities in the United States. New York City is at the top, but what other cities are in the top three? Sorry, not Boston, Chicago, or Baltimore. How about Philadelphia (home of Independence Hall) and Portland, Oregon (what? a town on the west coast!). If that surprised you, you’ll enjoying scanning the rest of the list (and perhaps rethink your summer travel plans). Here are the cities with more than 200 properties listed on the National Register:

- New York City, NY: 766

- Portland, OR: 571

- Philadelphia, PA: 555

- Washington, DC: 555

- Louisville, KY: 363

- Chicago, IL: 363

- St. Louis, MO: 357

- Price, UT: 342

- Denver, CO: 296

- Kansas City, MO: 295

- Boston, MA: 279

- Worchester, MA: 277

- Baltimore, MD: 276

- Cincinnati, OH: 274

- Detroit, MI: 260

- Houston, TX: 257

- Davenport, IA: 248

- Salt Lake City, UT: 245

- Cleveland, OH: 243

- Little Rock, AR: 233

- Indianapolis, IN: 228

- Atlanta, GA: 211

- Cambridge, MA: 209

If you were wondering about #8 Price, Utah, they’re mostly archaeological sites (such as Nine Mile Canyon, which has the largest concentration of rock art in the United States) added to the Register in the last five years.

Creating a 21st Century House Museum in San Francisco

Over the past two years, I’ve been working with San Francisco Heritage to explore how the Haas-Lilienthal House, the 1887 Queen Anne house it owns and operates in the Pacific Heights neighborhood, can engage the public and advance its citywide mission in ways that are both environmentally and financially sustainable.

Just as the Haas-Lilienthal House was rocked by a tremendous earthquake in 1906, so are historic sites today, although in a different manner. The economic downturn that began in 2008 threatens many preservation organizations, house museums, and historic sites, even those that have large endowments and attendance. But the change is bigger than the latest economic recession. Surveys over the past thirty years by the National Endowment for the Arts show that visitation rates at historic sites have fallen from 37 percent in 1982 to 25 percent in 2008, and that rate of decline has only accelerated in the last decade. The Haas-Lilienthal House is experiencing a long and steady decline in attendance—it’s fallen by more than 50 percent over the past thirty years. Historic sites not alone, however: concerts, dance performances, craft fairs, and sporting events have all seen similar declines in attendance.

As a result, many historic preservation organizations around the country are questioning the value of owning historic property. Guided tours and public programs do not generate sufficient revenue to properly maintain historic sites, so unloading them seems to be the only solution. But there are also significant disadvantages.

When a preservation organization owns an historic building, it instantly conveys credibility. (Would you trust a surgeon who has never held a scalpel?) Secondly, by owning and caring for an historic property, Continue reading

Taliesin West releases Preservation Master Plan

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation recently released the Preservation Master Plan for Taliesin West, a National Historic Landmark, which was established in 1937 as Frank Lloyd Wright’s winter home and studio, and the campus of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture. As part of the Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer lecture series, T. Gunny Harboe, preservation architect and founder of Chicago-based Harboe Architects, and the plan’s primary author, will present the major points of the Taliesin West plan on Monday, November 16 at 6:30 p.m. at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The lecture is free and reservations are not required.

I had an opportunity to use with the Preservation Master Plan as part of the interpretive planning work I’m doing at Taliesin West and it was immensely helpful in clarifying the significance and integrity of the many buildings at the site through a set of tiered levels: Continue reading

What Historic Sites Have Learned After 25 Years with ADA

This month marks the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which ensured equal access to persons with limited mobility, limited vision, limited hearing, and other disabilities. Shortly after this law was enacted in 1990, museums and historic sites were scrambling to figure out the consequences, especially the cost of installing ramps or hiring sign-language interpreters.

This month marks the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which ensured equal access to persons with limited mobility, limited vision, limited hearing, and other disabilities. Shortly after this law was enacted in 1990, museums and historic sites were scrambling to figure out the consequences, especially the cost of installing ramps or hiring sign-language interpreters.

Much of it also revolved thinking bigger and realizing that improving access for the disabled would improve the experience for everyone. For example, lever handles replaced doorknobs, which makes it easier to open a door when you’re carrying a package; enlarging type and increasing contrast on exhibit labels makes them easier to read (which I really appreciated as I grew older); and integrating ramps and removing thresholds is nice for visitors in wheelchairs and for staff who are always hauling tables and chairs for events. For several years, professional associations hosted sessions and printed books to explain ADA to help museums figure out how to respond in an effective and thoughtful manner.

Little discussed, however, is that the US Department of Justice (DOJ) also investigated several museums and historic sites for Continue reading

Openluchtmuseum Requires Mental Gymnastics in Historical Interpretation

The Openluchtmuseum, or Open Air Museum, in Arnhem in the Netherlands is one of the oldest outdoor/living history museums in the world. Opened in 1918, it preserves traditional and folk cultures by collecting vernacular buildings, furnishing them to specific periods, and using them to demonstrate historic crafts and skills. In the last decade, they’ve expanded these approaches by adding multimedia presentations along with interpreting the post-war period as part of an effort to create a national history museum interpreting the “Canon of the Netherlands” (the canon is a divergent idea worth investigating). In this post, I’ll examine their interpretation of the post-war period and in a later post discuss various unusual exhibition techniques.

At first glance, the Open Air Museum seems to be comprised of distinct clusters of farm buildings from a distinct region and time, where you can wander through houses and barns and watch someone in costume making brooms or working a plow. But the layering of history is complex and I found myself continually asking, “what time is it?” and “how are these things related?” to make sense of my visit. There are lots of historical anomalies, such as a 1960s phone booth in front of a 1910s train depot, but perhaps they’re not anomalies if you mentally reinterpret the scene by finding the overlapping period, such as the 1930s. These intellectual gymnastics don’t always work, but then again, the entire concept shaping the Open Air Museum allows for the artificial juxtaposition of historical places, times, and objects–which is what often happens in art museums and can also be bewildering (ever visit the Robert Lehman Gallery at the Met?)

The experience caused me to think hard about the role and purpose of interpretation Continue reading

Historic House Museums a Special Focus for the Public Historian

The May 2015 issue of the Public Historian was just released and provides a dozen articles related to historic house museums. Lisa Junkin Lopez, associate director of the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum and guest editor of this special issue, provides the criteria that helped her select the articles and her vision of historic house museums:

Though a number of sites have turned to revenue-generating activities like weddings and farmers’ markets to stay afloat, rigorous historical content has not necessarily been quashed in favor of parlor room cocktail hours and heirloom tomato beds. Many sites have recommitted to the project of excavating their own histories, digging deeper to find relevance with contemporary audiences and identifying new methods for engagement along the way.

The individual essays are case studies of various projects at historic house museums, but many question and even break the basic assumptions of museum practices and historic preservation standards. This shift will need to be watched because Continue reading

How to Get a Behind-the-Scenes Look at Historic New England

Historic New England presents its annual Program in New England Studies (PINES), an intensive week-long exploration of New England from Monday, June 15 to Saturday, June 20, 2015. PINES includes lectures by noted curators and architectural historians, workshops, behind-the-scenes tours, and special access to historic house museums and collections. The program offers a broad approach to teaching the history of New England culture through artifacts and architecture in a way that no other museum or historic site in the Northeast can match. It’s like the Attingham Summer School as a week in New England.

Historic New England presents its annual Program in New England Studies (PINES), an intensive week-long exploration of New England from Monday, June 15 to Saturday, June 20, 2015. PINES includes lectures by noted curators and architectural historians, workshops, behind-the-scenes tours, and special access to historic house museums and collections. The program offers a broad approach to teaching the history of New England culture through artifacts and architecture in a way that no other museum or historic site in the Northeast can match. It’s like the Attingham Summer School as a week in New England.

Examine New England history and material culture from the seventeenth century through the Colonial Revival with some of the country’s leading experts in regional architecture and decorative arts. Curators lecture on furniture, textiles, ceramics, and art, with information on history, craftsmanship, and changing methods of production. Architectural historians explore architecture starting with the seventeenth-century Massachusetts Bay style through the Federal and Georgian eras, to Gothic Revival and the Colonial Revival.

Expert presenters include: Continue reading