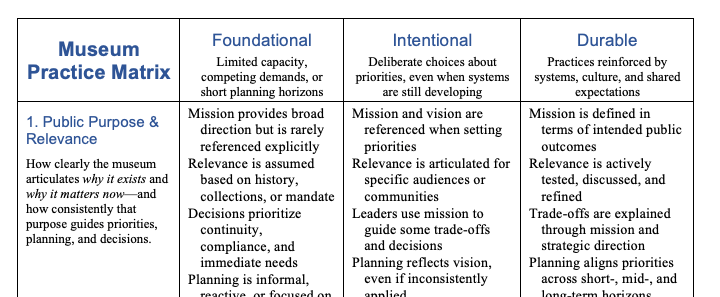

One of the things I keep returning to in my teaching and consulting is how much museum work actually lives along a spectrum—not in binary terms of success or failure, right or wrong, compliant or noncompliant.

This is one of the persistent challenges of working with professional standards. Standards are essential. They articulate shared values, define public trust, and help the field hold itself accountable. But by their nature, standards can imply an all-or-nothing logic: either you are doing the thing or you are not. And if you are not, that’s a problem.

Museum management, of course, is far more complex.

Museums and historic sites operate with widely varying levels of capacity, expertise, staffing, governance maturity, and external pressure. Boards change. Funding fluctuates. Crises intervene. Even within a single organization, some areas of work may be highly developed while others lag behind—not because of neglect or incompetence, but because of constrained resources and competing priorities.

Over time, I’ve become interested in how we might better describe and normalize that reality for the field—without lowering expectations or abandoning standards altogether.

Why a Matrix (Not a Scorecard)

In different contexts, I’ve heard similar tools described as rubrics, spectrums, continuums, or maturity models. In my own work, I’ve settled on calling this a matrix, for a very specific reason: it allows us to look across multiple areas of practice at once.

Once you do that, patterns start to emerge.

Continue reading